The Bible, The Qur’an, And Science

This article is a word document of a book by Dr. Maurice Bucaille published book called The Bible, The Qur’an and Science.

The Holy Scriptures Examined In The Light Of Modern Knowledge by Dr. Maurice Bucaille – Translated from French by Alastair D. Pannell and The Author

Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- The Old Testament

- The Books of the Old Testament

- The Old Testament and Science Findings

- Position Of Christian Authors With Regard To Scientific Error In The Biblical Texts

- Conclusions to the Old Testament

- The Gospels

- Historical Reminder Judeo-Christian and Saint Paul

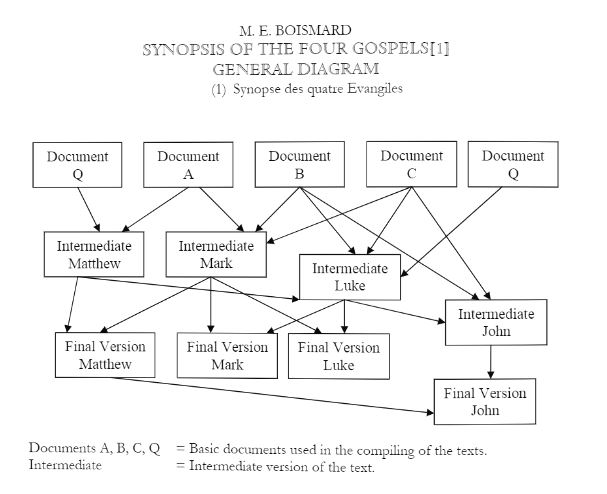

- The Four Gospels. Sources and History

- The Gospel According To Matthew

- The Gospel According To Mark

- The Gospel According To Luke

- The Gospel According To John

- Sources of the Gospels

- History of the Texts

- The Gospels and Modern Science. The General Genealogies of Jesus

- Contradictions and Improbabilities in the Descriptions

- Conclusions to The Gospels

- The Qur’an and Modern Science

- Authenticity of the Qur’an. How It Came To Be Written

- The Creation of the Heavens and the Earth

- Astronomy in the Qur’an

- The Earth

- The Animal and Vegetable Kingdoms

- Human Reproduction

- Qur’anic and Biblical Narrations

- The Flood

- The Exodus

- The Qur’an, Hadith and Modern Science

- General Conclusions

- Endnotes

- Back cover

Foreword

In his objective study of the texts, Maurice Bucaille clears away many preconceived ideas about the Old Testament, the Gospels and the Qur’an. He tries, in this collection of Writings, to separate what belongs to Revelation from what is the product of error or human interpretation. His study sheds new light on the Holy Scriptures. At the end of a gripping account, he places the Believer before a point of cardinal importance: the continuity of a Revelation emanating from the same God, with modes of expression that differ in the course of time. It leads us to meditate upon those factors which, in our day, should spiritually unite rather than divide-Jews, Christians and Muslims.

As a surgeon, Maurice Bucaille has often been in a situation where he was able to examine not only people’s bodies, but their souls. This is how he was struck by the existence of Muslim piety and by aspects of Islam which remain unknown to the vast majority of non-Muslims. In his search for explanations which are otherwise difficult to obtain, he learnt Arabic and studied the Qur’an. In it, he was surprised to find statements on natural phenomena whose meaning can only be understood through modern scientific knowledge.

He then turned to the question of the authenticity of the writings that constitute the Holy Scriptures of the monotheistic religions. Finally, in the case of the Bible, he proceeded to a confrontation between these writings and scientific data.

The results of his research into the Judeo-Christian Revelation and the Qur’an are set out in this book.

Introduction

Each of the three monotheistic religions possess its own collection of Scriptures. For the faithful-be they Jews, Christians or Muslims-these documents constitute the foundation of their belief. For them they are the material transcription of a divine Revelation; directly, as in the case of Abraham and Moses, who received the commandments from God Himself, or indirectly, as in the case of Jesus and Muhammad, the first of whom stated that he was speaking in the name of the Father, and the second of whom transmitted to men the Revelation imparted to him by Archangel Gabriel.

If we take into consideration the objective facts of religious history, we must place the Old Testament, the Gospels and the Qur’an on the same level as being collections of written Revelation. Although this attitude is in principle held by Muslims, the faithful in the West under the predominantly Judeo-Christian influence refuse to ascribe to the Qur’an the character of a book of Revelation.

Such an attitude may be explained by the position each religious community adopts towards the other two with regard to the Scriptures.

Judaism has as its holy book the Hebraic Bible. This differs from the Old Testament of the Christians in that the latter have included several books which did not exist in Hebrew. In practice, this divergence hardly makes any difference to the doctrine. Judaism does not however admit any revelation subsequent to its own.

Christianity has taken the Hebraic Bible for itself and added a few supplements to it. It has not however accepted all the published writings destined to make known to men the Mission of Jesus. The Church has made incisive cuts in the profusion of books relating the life and teachings of Jesus. It has only preserved a limited number of writings in the New Testament, the most important of which are the four Canonic Gospels. Christianity takes no account of any revelation subsequent to Jesus and his Apostles. It therefore rules out the Qur’an.

The Qur’anic Revelation appeared six centuries after Jesus. It resumes numerous data found in the Hebraic Bible and the Gospels since it quotes very frequently from the ‘Torah'[1] and the ‘Gospels.’ The Qur’an directs all Muslims to believe in the Scriptures that precede it (sura 4, verse 136). It stresses the important position occupied in the Revelation by God’s emissaries, such as Noah, Abraham, Moses, the Prophets and Jesus, to whom they allocate a special position. His birth is described in the Qur’an, and likewise in the Gospels, as a supernatural event. Mary is also given a special place, as indicated by the fact that sura 19 bears her name.

The above facts concerning Islam are not generally known in the West. This is hardly surprising, when we consider the way so many generations in the West were instructed in the religious problems facing humanity and the ignorance in which they were kept about anything related to Islam. The use of such terms as ‘Mohammedan religion’ and ‘Mohammedans’ has been instrumental-even to the present day-in maintaining the false notion that beliefs were involved that were spread by the work of man among which God (in the Christian sense) had no place. Many cultivated people today are interested in the philosophical, social and political aspects of Islam, but they do not pause to inquire about the Islamic Revelation itself, as indeed they should.

In what contempt the Muslims are held by certain Christian circles! I experienced this when I tried to start an exchange of ideas arising from a comparative analysis of Biblical and Qur’anic stories on the same theme. I noted a systematic refusal, even for the purposes of simple reflection, to take any account of what the Qur’an had to say on the subject in hand. It is as if a quote from the Qur’an were a reference to the Devil!

A noticeable change seems however to be under way these days at the highest levels of the Christian world. The Office for Non-Christian Affairs at the Vatican has produced a document result. from the Second Vatican Council under the French title Orientations pour un dialogue entre Chrétiens et Musulmans[2]

(Orientations for a Dialogue between Christians and Muslims), third French edition dated 1970, which bears witness to the profound change in official attitude. Once the document has invited the reader to clear away the “out-dated image, inherited from the past, or distorted by prejudice and slander” that Christians have of Islam, the Vatican document proceeds to “recognize the past injustice towards the Muslims for which the West, with its Christian education, is to blame”. It also criticizes the misconceptions Christians have been under concerning Muslim fatalism, Islamic legalism, fanaticism, etc. It stresses belief in unity of God and reminds us how surprised the audience was at the Muslim University of Al Azhar, Cairo, when Cardinal Koenig proclaimed this unity at the Great Mosque during an official conference in March, 1969. It reminds us also that the Vatican Office in 1967 invited Christians to offer their best wishes to Muslims at the end of the Fast of Ramadan with “genuine religious worth”.

Such preliminary steps towards a closer relationship between the Roman Catholic Curia and Islam have been followed by various manifestations and consolidated by encounters between the two. There has been, however, little publicity accorded to events of such great importance in the western world, where they took place and where there are ample means of communication in the form of press, radio and television.

The newspapers gave little coverage to the official visit of Cardinal Pignedoli, the President of the Vatican Office of Non-Christian Affairs, on 24th April, 1974, to King Faisal of Saudi Arabia. The French newspaper Le Monde on 25th April, 1974, dealt with it in a few lines. What momentous news they contain, however, when we read how the Cardinal conveyed to the Sovereign a message from Pope Paul VI expressing “the regards of His Holiness, moved by a profound belief in the unification of Islamic and Christian worlds in the worship of a single God, to His Majesty King Faisal as supreme head of the Islamic world”. Six months later, in October 1974, the Pope received the official visit to the Vatican of the Grand Ulema of Saudi Arabia. It occasioned a dialogue between Christians and Muslims on the “Cultural Rights of Man in Islam”. The Vatican newspaper, Observatore Romano, on 26th October, 1974, reported this historic event in a front page story that took up more space than the report on the closing day of the meeting held by the Synod of Bishops in Rome.

The Grand Ulema of Saudi Arabia were afterwards received by the Ecumenical Council of Churches of Geneva and by the Lord Bishop of Strasbourg, His Grace Elchinger. The Bishop invited them to join in midday prayer before him in his cathedral. The fact that the event Was reported seems to be more on account of its unusual nature than because of its considerable religious significance. At all events, among those whom I questioned about this religious manifestation, there were very few who replied that they were aware of it.

The open-minded attitude Pope Paul VI has towards Islam will certainly become a milestone in the relations between the two religions. He himself Mid that he was “moved by a profound belief in the unification of the Islamic and Christian worlds in the worship of a single God”. This reminder of the sentiments of the head of the Catholic Church concerning Muslims is indeed necessary. Far too many Christians, brought up in a spirit of open hostility, are against any reflection about Islam on principle. The Vatican document notes this with regret. It is on account of this that they remain totally ignorant of what Islam is in reality, and retain notions about the Islamic Revelation which are entirely mistaken.

Nevertheless, when studying an aspect of the Revelation of a monotheistic religion, it seems quite in order to compare what the other two have to say on the same subject. A comprehensive study of a problem is more interesting than a compartmentalized one. The confrontation between certain subjects dealt with in the Scriptures and the facts of 20th century science will therefore, in this work, include all three religions. In addition it will be useful to realize that the three religions should form a tighter block by virtue of their closer relationship at a time when they are all threatened by the onslaught of materialism. The notion that science and religion are incompatible is as equally prevalent in countries under the Judeo-Christian influence as in the world of Islam-especially in scientific circles. If this question were to be dealt with comprehensively, a series of lengthy exposes would be necessary. In this work, I intend to tackle only one aspect of it: the examination of the Scriptures themselves in the light of modern scientific knowledge.

Before proceeding with our task, we must ask a fundamental question: How authentic are today’s texts? It is a question which entails an examination of the circumstances surrounding their composition and the way in which they have come down to us.

In the West the critical study of the Scriptures is something quite recent. For hundreds of years people were content to accept the Bible-both Old and New Testaments-as it was. A reading produced nothing more than remarks vindicating it. It would have been a sin to level the slightest criticism at it. The clergy were priviledged in that they were easily able to have a comprehensive knowledge of the Bible, while the majority of laymen heard only selected readings as part of a sermon or the liturgy.

Raised to the level of a specialized study, textual criticism has been valuable in uncovering and disseminating problems which are often very serious. How disappointing it is therefore to read works of a so-called critical nature which, when faced with very real problems of interpretation, merely provide passages of an apologetical nature by means of which the author contrives to hide his dilemma. Whoever retains his objective judgment and power of thought at such a moment will not find the improbabilities and contradictions any the less persistent. One can only regret an attitude which, in the face of all logical reason, upholds certain passages in the Biblical Scriptures even though they are riddled with errors. It can exercise an extremely damaging influence upon the cultivated mind with regard to belief in God. Experience shows however that even if the few are able to distinguish fallacies of this kind, the vast majority of Christians have never taken any account of such incompatibilities with their secular knowledge, even though they are often very elementary.

Islam has something relatively comparable to the Gospels in some of the Hadiths. These are the collected sayings of Muhammad and stories of his deeds. The Gospels are nothing other than this for Jesus. Some of the collections of Hadiths were written decades after the death of Muhammad, just as the Gospels were written decades after Jesus. In both cases they bear human witness to events in the past. We shall see how, contrary to what many people think, the authors of the four Canonic Gospels were not the witnesses of the events they relate. The same is true of the Hadiths referred to at the end of this book.

Here the comparison must end because even if the authenticity of such-and-such a Hadith has been discussed and is still under discussion, in the early centuries of the Church the problem of the vast number of Gospels was definitively decided. Only four of them were proclaimed official, or canonic, in spite of the many points on which they do not agree, and order was given for the rest to be concealed; hence the term ‘Apocrypha’.

Another fundamental difference in the Scriptures of Christianity and Islam is the fact that Christianity does not have a text which is both revealed and written down. Islam, however, has the Qur’an which fits this description.

The Qur’an is the expression of the Revelation made to Muhammad by the Archangel Gabriel, which was immediately taken down, and was memorized and recited by the faithful in their prayers, especially during the month of Ramadan. Muhammad himself arranged it into suras, and these were collected soon after the death of the Prophet, to form, under the rule of Caliph Uthman (12 to 24 years after the Prophet’s death), the text we know today.

In contrast to this, the Christian Revelation is based on numerous indirect human accounts. We do not in fact have an eyewitness account from the life of Jesus, contrary to what many Christians imagine. The question of the authenticity of the Christian and Islamic texts has thus now been formulated.

The confrontation between the texts of the Scriptures and scientific data has always provided man with food for thought.

It was at first held that corroboration between the scriptures and science was a necessary element to the authenticity of the sacred text. Saint Augustine, in letter No. 82, which we shall quote later on, formally established this principle. As science progressed however it became clear that there were discrepancies between Biblical Scripture and science. It was therefore decided that comparison would no longer be made. Thus a situation arose which today, we are forced to admit, puts Biblical exegetes and scientists in opposition to one another. We cannot, after all, accept a divine Revelation making statements which are totally inaccurate. There was only one way of logically reconciling the two; it lay in not considering a passage containing unacceptable scientific data to be genuine. This solution was not adopted. Instead, the integrity of the text was stubbornly maintained and experts were obliged to adopt a position on the truth of the Biblical Scriptures which, for the scientist, is hardly tenable.

Like Saint Augustine for the Bible, Islam has always assumed that the data contained in the Holy Scriptures were in agreement with scientific fact. A modern examination of the Islamic Revelation has not caused a change in this position. As we shall see later on, the Qur’an deals with many subjects of interest to science, far more in fact than the Bible. There is no comparison between the limited number of Biblical statements which lead to a confrontation With science, and the profusion of subjects mentioned in the Qur’an that are of a scientific nature. None of the latter can be contested from a scientific point of view. this is the basic fact that emerges from our study. We shall see at the end of this work that such is not the case for the Hadiths. These are collections of the Prophet’s sayings, set aside from the Qur’anic Revelation, certain of which are scientifically unacceptable. The Hadiths in question have been under study in accordance with the strict principles of the Qur’an which dictate that science and reason should always be referred to, if necessary to deprive them of any authenticity.

These reflections on the scientifically acceptable or unacceptable nature of a certain Scripture need some explanation. It must be stressed that when scientific data are discussed here, what is meant is data definitely established. This consideration rules out any explanatory theories, once useful in illuminating a phenomenon and easily dispensed with to make way for further explanations more in keeping with scientific progress. What I intend to consider here are incontrovertible facts and even if science can only provide incomplete data, they will nevertheless be sufficiently well established to be used Without fear of error.

Scientists do not, for example, have even an approximate date for man’s appearance on Earth. They have however discovered remains of human works which we can situate beyond a shadow of a doubt at before the tenth millenium B.C. Hence we cannot consider the Biblical reality on this subject to be compatible with science. In the Biblical text of Genesis, the dates and genealogies given would place man’s origins (i.e. the creation of Adam) at roughly thirty-seven centuries B.C. In the future, science may be able to provide us with data that are more precise than our present calculations, but we may rest assured that it will never tell us that man first appeared on Earth 6,786 years ago, as does the Hebraic calendar for 1976. The Biblical data concerning the antiquity of man are therefore inaccurate.

This confrontation with science excludes all religious problems in the true sense of the word. Science does not, for example, have any explanation of the process whereby God manifested Himself to Moses. The same may be said for the mystery surrounding the manner in which Jesus was born in the absence of a biological father. The Scriptures moreover give no material explanation of such data. This present study is concerned With what the Scriptures tell us about extremely varied natural phenomena, which they surround to a lesser or greater extent with commentaries and explanations. With this in mind, we must note the contrast between the rich abundance of information on a given subject in the Qur’anic Revelation and the modesty of the other two revelations on the same subject.

It was in a totally objective spirit, and without any preconceived ideas that I first examined the Qur’anic Revelation. I was looking for the degree of compatibility between the Qur’anic text and the data of modern science. I knew from translations that the Qur’an often made allusion to all sorts of natural phenomena, but I had only a summary knowledge of it. It was only when I examined the text very closely in Arabic that I kept a list of them at the end of which I had to acknowledge the evidence in front of me: the Qur’an did not contain a single statement that was assailable from a modern scientific point of view.

I repeated the same test for the Old Testament and the Gospels, always preserving the same objective outlook. In the former I did not even have to go beyond the first book, Genesis, to find statements totally out of keeping With the cast-iron facts of modern science.

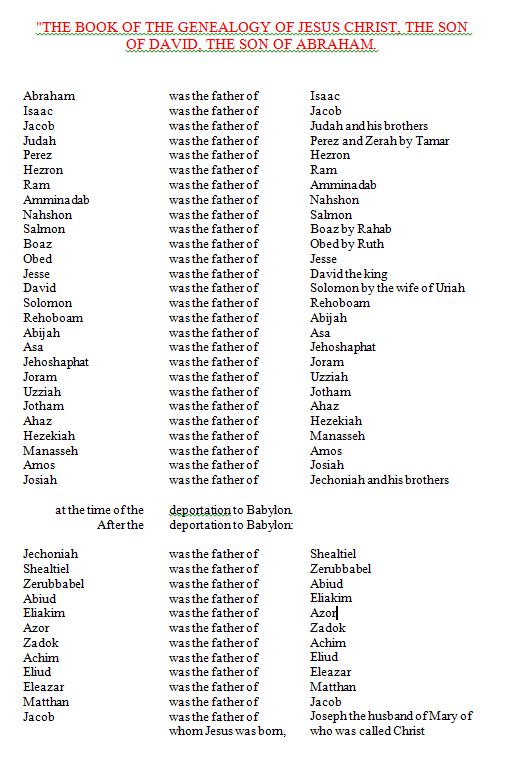

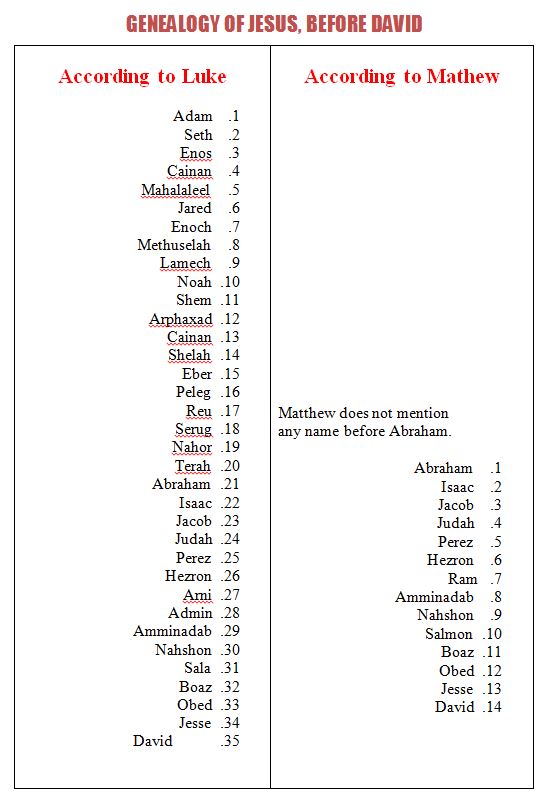

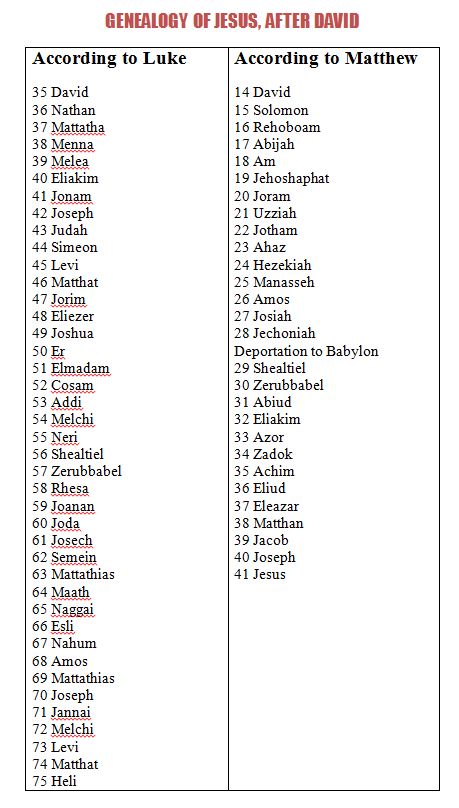

On opening the Gospels, one is immediately confronted with a serious problem. On the first page we find the genealogy of Jesus, but Matthew’s text is in evident contradiction to Luke’s on the same question. There is a further problem in that the latter’s data on the antiquity of man on Earth are incompatible with modern knowledge.

The existence of these contradictions, improbabilities and incompatibilities does not seem to me to detract from the belief in God. They involve only man’s responsibility. No one can say what the original texts might have been, or identify imaginative editing, deliberate manipulations of them by men, or unintentional modification of the Scriptures. What strikes us today. when we realize Biblical contradictions and incompatibilities with well-established scientific data, is how specialists studying the texts either pretend to be unaware of them, or else draw attention to these defects then try to camouflage them with dialectic acrobatics. When we come to the Gospels according to Matthew and John, I shall provide examples of this brilliant use of apologetical turns of phrase by eminent experts in exegesis. Often the attempt to camouflage an improbability or a contradiction, prudishly called a ‘difficulty’, is successful. This explains why so many Christians are unaware of the serious defects contained in the Old Testament and the Gospels. The reader will find precise examples of these in the first and second parts of this work.

In the third part, there is the illustration of an unusual application of science to a holy Scripture, the contribution of modern secular knowledge to a better understanding of certain verses in the Qur’an which until now have remained enigmatic, if not incomprehensible. Why should we be surprised at this when we know that, for Islam, religion and science have always been considered twin sisters? From the very beginning, Islam directed people to cultivate science; the application of this precept brought with it the prodigious strides in science taken during the great era of Islamic civilization, from which, before the Renaissance, the West itself benefited. In the confrontation between the Scriptures and science a high point of understanding has been reached owing to the light thrown on Qur’anic passages by modern scientific knowledge. Previously these passages were obscure owning to the non-availability of knowledge which could help interpret them.

The Old Testament

General Outlines

Who is the author of the Old Testament?

The Bible The Qur’an And Science

One wonders how many readers of the Old Testament, if asked the above question, would reply by repeating what they had read in the introduction to their Bible. They might answer that, even though it was written by men inspired by the Holy Ghost, the author was God.

Sometimes, the author of the Bible’s presentation confines himself to informing his reader of this succinct observation which puts an end to all further questions. Sometimes he corrects it by warning him that details may subsequently have been added to the primitive text by men, but that nonetheless, the litigious character of a passage does not alter the general “truth’ that proceeds from it. This “truth’ is stressed very heavily. The Church Authorities answer for it, being the only body, With the assistance of the Holy Ghost, able to enlighten the faithful on such points. Since the Councils held in the Fourth century, it was the Church that issued the list of Holy Books, ratified by the Councils of Florence (1441), Trent (1546), and the First Vatican Council (1870), to form what today is known as the Canon. Just recently, after so many encyclicals, the Second Vatican Council published a text concerning the Revelation which is extremely important. It took three years (1962-1966) of strenuous effort to produce. The vast majority of the Bible’s readers who find this highly reassuring information at the head of a modern edition have been quite satisfied with the guarantees of authenticity made over past centuries and have hardly thought it possible to debate them.

When one refers however to works written by clergymen, not meant for mass publication, one realizes that the question concerning the authenticity of the books in the Bible is much more complex than one might suppose a priori. For example, when one consults the modern publication in separate installments of the Bible in French translated under the guidance of the Biblical School of Jerusalem[3], the tone appears to be very different. One realizes that the Old Testament, like the New Testament, raises problems with controversial elements that, for the most part, the authors of commentaries have not concealed.

We also find highly precise data in more condensed studies of a very objective nature, such as Professor Edmond Jacob’s study. The Old Testament (L’Ancien Testament)[4]. This book gives an excellent general view.

Many people are unaware, and Edmond Jacob points this out, that there were originally a number of texts and not just one. Around the Third century B.C., there were at least three forms of the Hebrew text: the text which was to become the Masoretic text, the text which was used, in part at least, for the Greek translation, and the Samaritan Pentateuch. In the First century B.C., there was a tendency towards the establishment of a single text, but it was not until a century after Christ that the Biblical text was definitely established.

If we had had the three forms of the text, comparison would have been possible, and we could have reached an opinion concerning what the original might have been. Unfortunately, we do not have the slightest idea. Apart from the Dead Sea Scrolls (Cave of Qumran) dating from a pre-Christian era near the time of Jesus, a papyrus of the Ten Commandments of the Second century A.D. presenting variations from the classical text, and a few fragments from the Fifth century A.D. (Geniza of Cairo) , the oldest Hebrew text of the Bible dates from the Ninth century A.D.

The Septuagint was probably the first translation in Greek. It dates from the Third century B.C. and was written by Jews in Alexandria. It Was on this text that the New Testament was based. It remained authoritative until the Seventh century A.D. The basic Greek texts in general use in the Christian world are from the manuscripts catalogued under the title Codex Vaticanus in the Vatican City and Codex Sinaiticus at the British Museum, London. They date from the Fourth century A.D.

At the beginning of the Fifth century A.D., Saint Jerome was able to produce a text in latin using Hebrew documents. It was later to be called the Vulgate on account of its universal distribution after the Seventh century A.D.

For the record, we shall mention the Aramaic version and the Syriac (Peshitta) version, but these are incomplete.

All of these versions have enabled specialists to piece together so-called ‘middle-of-the-road’ texts, a sort of compromise between the different versions. Multi-lingual collections have also been produced which juxtapose the Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Syriac, Aramaic and even Arabic versions. This is the case of the famous Walton Bible (London, 1667). For the sake of completeness, let us mention that diverging Biblical conceptions are responsible for the fact that the various Christian churches do not all accept exactly the same books and have not until now had identical ideas on translation into the same language. The Ecumenical Translation of the Old Testament is a work of unification written by numerous Catholic and Protestant experts now nearing completion[5] and should result in a work of synthesis.

Thus the human element in the Old Testament is seen to be quite considerable. It is not difficult to understand why from version to version, and translation to translation, with all the corrections inevitably resulting, it was possible for the original text to have been transformed during the course of more than two thousand years.

ORIGINS OF THE BIBLE

Before it became a collection of books, it was a folk tradition that relied entirely upon human memory, originally the only means of passing on ideas. This tradition was sung.

“At an elementary stage, writes E. Jacob, every people sings; in Israel, as elsewhere, poetry preceded prose. Israel sang long and well; led by circumstances of his history to the heights of joy and the depths of despair, taking part with intense feeling in all that happened to it, for everything in their eyes had a sense, Israel gave its song a wide variety of expression”. They sang for the most diverse reasons and E. Jacob mentions a number of them to which we find the accompanying songs in the Bible: eating songs, harvest songs, songs connected with work, like the famous Well Song (Numbers 21, 17), wedding songs, as in the Song of Songs, and mourning songs. In the Bible there are numerous songs of war and among these we find the Song of Deborah (Judges 5, 1-32) exalting Israel’s victory desired and led by Yahweh Himself, (Numbers 10, 35); “And whenever the ark (of alliance) set out, Moses said, ‘Arise, oh Yahweh, and let thy enemies be scattered; and let them that hate thee nee before thee”.

There are also the Maxims and Proverbs (Book of Proverbs, Proverbs and Maxims of the Historic Books), words of blessing and curse, and the laws decreed to man by the Prophets on reception of their Divine mandate.

E. Jacobs notes that these words were either passed down from family to family or channelled through the sanctuaries in the form of an account of the history of God’s chosen people. History quickly turned into fable, as in the Fable of Jotham (Judges 9, 7-21), where “the trees went forth to anoint a king over them; and they asked in turn the olive tree, the fig tree, the vine and the bramble”, which allows E. Jacob to note “animated by the need to tell a good story, the narration was not perturbed by subjects or times whose history was not well known”, from which he concludes:

“It is probable that what the Old Testament narrates about Moses and the patriarchs only roughly corresponds to the succession of historic facts. The narrators however, even at the stage of oral transmission, were able to bring into play such grace and imagination to blend between them highly varied episodes, that when all is said and done, they were able to present as a history that was fairly credible to critical thinkers what happened at the beginning of humanity and the world”.

There is good reason to believe that after the Jewish people settled in Canaan, at the end of the Thirteenth century B.C., writing was used to preserve and hand down the tradition. There was not however complete accuracy, even in what to men seems to demand the greatest durability, i.e. the laws. Among these, the laws which are supposed to have been written by God’s own hand, the Ten Commandments, were transmitted in the Old Testament in two versions; Exodus (20,1-21) and Deuteronomy (5, 1-30). They are the same in spirit, but the variations are obvious. There is also a concern to keep a large written record of contracts, letters, lists of personalities (Judges, high city officials, genealogical tables), lists of offerings and plunder. In this way, archives were created which provided documentation for the later editing of definitive works resulting in the books we have today. Thus in each book there is a mixture of different literary genres: it can be left to the specialists to find the reasons for this odd assortment of documents.

The Old Testament is a disparate whole based upon an initially oral tradition. It is interesting therefore to compare the process by which it was constituted with what could happen in another period and another place at the time when a primitive literature was born.

Let us take, for example, the birth of French literature at the time of the Frankish Royalty. The same oral tradition presided over the preservation of important deeds: wars, often in the defense of Christianity, various sensational events, where heroes distinguished themselves, that were destined centuries later to inspire court poets, chroniclers and authors of various ‘cycles’. In this way, from the Eleventh century A.D. onwards, these narrative poems, in which reality is mixed with legend, were to appear and constitute the first monument in epic poetry. The most famous of all is the Song of Roland (La Chanson de Roland) a biographical chant about a feat of arms in which Roland was the commander of Emperor Charlemagne’s rearguard on its way home from an expedition in Spain. The sacrifice of Roland is not just an episode invented to meet the needs of the story. It took place on 15th August, 778. In actual fact it was an attack by Basques living in the mountains. This literary work is not just legend ; it has a historical basis, but no historian would take it literally.

This parallel between the birth of the Bible and a secular literature seems to correspond exactly with reality. It is in no way meant to relegate the whole Biblical text as we know it today to the store of mythological collections, as do so many of those who systematically negate the idea of God. It is perfectly possible to believe in the reality of the Creation, God’s transmission to Moses of the Ten Commandments, Divine intercession in human affairs, e.g. at the time of Solomon. This does not stop us, at the same time, from considering that what has been conveyed to us is the gist of these facts, and that the detail in the description should be subjected to rigorous criticism, the reason for this being that the element of human participation in the transcription of originally oral traditions is so great

The Books of the Old Testament

The Old Testament is a collection of works of greatly differing length and many different genres. They were written in several languages over a period of more than nine hundred years, based on oral traditions. Many of these works were corrected and completed in accordance with events or special requirements, often at periods that were very distant from one another.

This copious literature probably flowered at the beginning of the Israelite Monarchy, around the Eleventh century B.C. It was at this period that a body of scribes appeared among the members of the royal household. They were cultivated men whose role was not limited to writing. The first incomplete writings, mentioned in the preceding chapter, may date from this period. There was a special reason for writing these works down; there were a certain number of songs (mentioned earlier), the prophetic oracles of Jacob and Moses, the Ten Commandments and, on a more general level, the legislative texts which established a religious tradition before the formation of the law. All these texts constitute fragments scattered here and there throughout the various collections of the Old Testament.

It was not until a little later, possibly during the Tenth century B.C., that the so-called ‘Yahvist'[6] text of the Pentateuch was written. This text was to form the backbone of the first five books ascribed to Moses. Later, the so-called ‘Elohist'[7] text was to be added, and also the so-called ‘Sacerdotal'[8] version. The initial Yahvist text deals with the origins of the world up to the death of Jacob. This text comes from the southern kingdom, Judah.

At the end of the Ninth century and in the middle of the Eighth century B.C., the prophetic influence of Elias and Elisha took shape and spread. We have their books today. This is also the time of the Elohist text of the Pentateuch which covers a much smaller period than the Yahvist text because it limits itself to facts relating to Abraham, Jacob and Joseph. The books of Joshua and Judges date from this time.

The Eighth century B.C. saw the appearance of the writerprophets: Amos and Hosea in Israel, and Michah in Judah.

In 721 B.C., the fall of Samaria put an end to the Kingdom of Israel. The Kingdom of Judah took over its religious heritage. The collection of Proverbs dates from this period, distinguished in particular by the fusion into a single book of the Yahvist and Elohist texts of the Pentateuch; in this way the Torah was constituted. Deuteronomy was written at this time.

In the second half of the Seventh century B.C., the reign of Josiah coincided with the appearance of the prophet Jeremiah, but his work did not take definitive shape until a century later.

Before the first deportation to Babylon in 598 B.C., there appeared the Books of Zephaniah, Nahum and Habakkuk. Ezekiel was already prophesying during this first deportation. The fall of Jerusalem in 587 B.C. marked the beginning of the second deportation which lasted until 538 B.C.

The Book of Ezekiel, the last great prophet and the prophet of exile, was not arranged into its present form until after his death by the scribes that were to become his spiritual inheritors. These same scribes were to resume Genesis in a third version, the so-called ‘Sacerdotal’ version, for the section going from the Creation to the death of Jacob. In this way a third text was to be inserted into the central fabric of the Yahvist and Elohist texts of the Torah. We shall see later on, in the books written roughly two and four centuries earlier, an aspect of the intricacies of this third text. It was at this time that the Lamentations appeared.

On the order of Cyrus, the deportation to Babylon came to an end in 538 B.C. The Jews returned to Palestine and the Temple at Jerusalem was rebuilt. The prophets’ activities began again, resulting in the books of Haggai, Zechariah, the third book of Isaiah, Malachi, Daniel and Baruch (the last being in Greek). The period following the deportation is also the period of the Books of Wisdom: Proverbs was written definitively around 480 B.C., Job in the middle of the Fifth century B.C., Ecclesiastes or Koheleth dates from the Third century B.C., as do the Song of Songs, Chronicles I & II, Ezra and Nehemiah; Ecclesiasticus or Sirah appeared in the Second century B.C.; the Book of Wisdom and the Book of Maccabees I & II were written one century before Christ. The Books of Ruth, Esther and Jonah are not easily datable. The same is true for Tobit and Judith. All these dates are given on the understanding that there may have been subsequent adaptations, since it was only circa one century before Christ that form was first given to the writings of the Old Testament. For many this did not become definitive until one century after Christ.

Thus the Old Testament appears as a literary monument to the Jewish people, from its origins to the coming of Christianity. The books it consists of were written, completed and revised between the Tenth and the First centuries B.C. This is in no way a personal point of view on the history of its composition. The essential data for this historical survey were taken from the entry The Bible in the Encyclopedia Universalis[9] by J. P. Sandroz, a professor at the Dominican Faculties, Saulchoir. To understand what the Old Testament represents, it is important to retain this information, correctly established today by highly qualified specialists.

A Revelation is mingled in all these writings, but all we possess today is what men have seen fit to leave us. These men manipulated the texts to please themselves, according to the circumstances they were in and the necessities they had to meet.

When these objective data are compared with those found in various prefaces to Bibles destined today for mass publication, one realizes that facts are presented in them in quite a different way. Fundamental facts concerning the writing of the books are passed over in silence, ambiguities which mislead the reader are maintained, facts are minimalised to such an extent that a false idea of reality is conveyed. A large number of prefaces or introductions to the Bible misrepresent reality in this way. In the case of books that were adapted several times (like the Pentateuch), it is said that certain details may have been added later on. A discussion of an unimportant passage of a book is introduced, but crucial facts warranting lengthy expositions are passed over in silence. It is distressing to see such inaccurate information on the Bible maintained for mass publication.

THE TORAH OR PENTATEUCH

Torah is the Semitic name.

The Greek expression, which in English gives us ‘Pentateuch’, designates a work in five parts; Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. These were to form the five primary elements of the collection of thirty-nine volumes that makes up the Old Testament.

This group of texts deals with the origins of the world up to the entry of the Jewish people into Canaan, the land promised to them after their exile in Egypt, more precisely until the death of Moses. The narration of these facts serves however as a general framework for a description of the provisions made for the religious and social life of the Jewish people, hence the name Law or Torah.

Judaism and Christianity for many centuries considered that the author was Moses himself. Perhaps this affirmation was based on the fact that God said to Moses (Exodus 17, 14): “Write this (the defeat of Amalek) as a memorial in a book”, or again, talking of the Exodus from Egypt, “Moses wrote down their starting places” (Numbers 33, 2), and finally “And Moses wrote this law” (Deuteronomy 31, 9). From the First century B.C. onwards, the theory that Moses wrote the Pentateuch was upheld; Flavius Josephus and Philo of Alexandria maintain it.

Today, this theory has been completely abandoned; everybody is in agreement on this point. The New Testament nevertheless ascribes the authorship to Moses. Paul, in his Letter to the Romans (10, 5) quoting from Leviticus, affirms that “Moses writes that the man who practices righteousness which is based on the law . . .” etc. John, in his Gospel (5,46-47), makes Jesus say the following: “If you believed Moses, you would believe me, for he wrote of me. But if you do not believe his writings, how will you believe my words?” We have here an example of editing, because the Greek word that corresponds to the original (written in Greek) is episteuete, so that the Evangelist is putting an affirmation into Jesus’s mouth that is totally wrong: the following demonstrates this.

I am borrowing the elements of this demonstration from Father de Vaux, Head of the Biblical School of Jerusalem. He prefaced his French translation of Genesis in 1962 with a General Introduction to the Pentateuch which contained valuable arguments. These ran contrary to the affirmations of the Evangelists on the authorship of the work in question. Father de Vaux reminds us that the “Jewish tradition which was followed by Christ and his Apostles” was accepted up to the end of the Middle Ages. The only person to contest this theory was Abenezra in the Twelfth century. It was in the Sixteenth century that Calstadt noted that Moses could not have written the account of his own death in Deuteronomy (34, 5-12). The author then quotes other critics who refuse to ascribe to Moses a part, at least, of the Pentateuch. It was above all the work of Richard Simon, father of the Oratory, Critical History of the Old Testament (Histoire critique du Vieux Testament) 1678, that underlined the chronological difficulties, the repetitions, the confusion of the stories and stylistic differences in the Pentateuch. The book caused a scandal. R. Simon’s line of argument was barely followed in history books at the beginning of the Eighteenth century. At this time, the references to antiquity very often proceeded from what “Moses had written”.

One can easily imagine how difficult it was to combat a legend strengthened by Jesus himself who, as we have seen, supported it in the New Testament. It is to Jean Astruc, Louis XV’s doctor, that we owe the decisive argument.

By publishing, in 1753, his Conjectures on the original writings which it appears Moses used to compose the Book of Genesis (Conjectures sur les Mèmoires originaux dont il parait que Moyse s’est servi pour composer le livre de la Genèse), he placed the accent on the plurality of sources. He was probably not the first to have noticed it, but he did however have the courage to make public an observation of prime importance: two texts, each denoted by the way in which God was named either Yahweh or Elohim, were present side by side in Genesis. The latter therefore contained two juxtaposed texts. Eichorn (1780-1783) made the same discovery for the other four books; then Ilgen (1798) noticed that one of the texts isolated by Astruc, the one where God is named Elohim, was itself divided into two. The Pentateuch literally fell apart.

The Nineteenth century saw an even more minute search into the sources. In 1854, four sources were recognised. They were called the Yahvist version, the Elohist version, Deuteronomy, and the Sacerdotal version. It was even possible to date them:

- The Yahvist version was placed in the Ninth century B.C. (written in Judah)

- The Elohist version was probably a little more recent (written in Israel)

- Deuteronomy was from the Eighth century B.C. for some (E. Jacob) , and from the time of Josiah for others (Father de Vaux)

- The Sacerdotal version came from the period of exile or after the exile: Sixth century B.C.

It can be seen that the arrangement of the text of the Pentateuch spans at least three centuries.

The problem is, however, even more complex. In 1941, A. Lods singled out three sources in the Yahvist version, four in the Elohist version, six in Deuteronomy, nine in the Sacerdotal version, “not including the additions spread out among eight different authors” writes Father de Vaux. More recently, it has been thought that “many of the constitutions or laws contained in the Pentateuch had parallels outside the Bible going back much further than the dates ascribed to the documents themselves” and that “many of the stories of the Pentateuch presupposed a background that was different from-and older than-the one from which these documents were supposed to have come”. This leads on to “an interest in the formation of traditions”. The problem then appears so complicated that nobody knows where he is anymore.

The multiplicity of sources brings with it numerous disagreements and repetitions. Father de Vaux gives examples of this overlapping of traditions in the case of the Flood, the kidnapping of Joseph, his adventures in Egypt, disagreement of names relating to the same character, differing descriptions of important events.

Thus the Pentateuch is shown to be formed from various traditions brought together more or less skillfully by its authors. The latter sometimes juxtaposed their compilations and sometimes adapted the stories for the sake of synthesis. They allowed improbabilities and disagreements to appear in the texts, however, which have led modern man to the objective study of the sources.

As far as textual criticism is concerned, the Pentateuch provides what is probably the most obvious example of adaptations made by the hand of man. These were made at different times in the history of the Jewish people, taken from oral traditions and texts handed down from preceding generations. It was begun in the Tenth or Ninth century B.C. with the Yahvist tradition which took the story from its very beginnings. The latter sketches Israel’s own particular destiny to “fit it back into God’s Grand Design for humanity” (Father de Vaux). It was concluded in the Sixth century B.C. with the Sacerdotal tradition that is meticulous in its precise mention of dates and genealogies.[10] Father de Vaux writes that “The few stories this tradition has of its own bear witness to legal preoccupations: Sabbatical rest at the completion of the Creation, the alliance with Noah, the alliance with Abraham and the circumcision, the purchase of the Cave of Makpela that gave the Patriarchs land in Canaan”. We must bear in mind that the Sacerdotal tradition dates from the time of the deportation to Babylon and the return to Palestine starting in 538 B.C. There is therefore a mixture of religious and purely political problems.

For Genesis alone, the division of the Book into three sources has been firmly established: Father de Vaux in the commentary to his translation lists for each source the passages in the present text of Genesis that rely on them. On the evidence of these data it is possible to pinpoint the contribution made by the various sources to any one of the chapters. For example, in the case of the Creation, the Flood and the period that goes from the Flood to Abraham, occupying as it does the first eleven chapters of Genesis, we can see alternating in the Biblical text a section of the Yahvist and a section of the Sacerdotal texts. The Elohist text is not present in the first eleven chapters. The overlapping of Yahvist and Sacerdotal contributions is here quite clear. For the Creation and up to Noah (first five chapter’s), the arrangement is simple: a Yahvist passage alternates with a Sacerdotal passage from beginning to end of the narration. For the Flood and especially chapters 7 and 8 moreover, the cutting of the text according to its source is narrowed down to very short passages and even to a single sentence. In the space of little more than a hundred lines of English text, the text changes seventeen times. It is from this that the improbabilities and contradictions arise when we read the present-day text. (see Table on page 15 for schematic distribution of sources)

THE HISTORICAL BOOKS

In these books we enter into the history of the Jewish people, from the time they came to the Promised Land (which is most likely to have been at the end of the Thirteenth century B.C.) to the deportation to Babylon in the Sixth century B.C.

Here stress is laid upon what one might call the ‘national event’ which is presented as the fulfillment of Divine word. In the narration however, historical accuracy has rather been brushed aside: a work such as the Book of Joshua complies first and foremost with theological intentions. With this in mind, E. Jacob underlines the obvious contradiction between archaeology and the texts in the case of the supposed destruction of Jericho and Ay.

The Book of Judges is centered on the defense of the chosen people against surrounding enemies and on the support given to them by God. The Book was adapted several times, as Father A. Lefèvre notes with great objectivity in his Preamble to the Crampon Bible. the various prefaces in the text and the appendices bear witness to this. The story of Ruth is attached to the narrations contained in Judges.

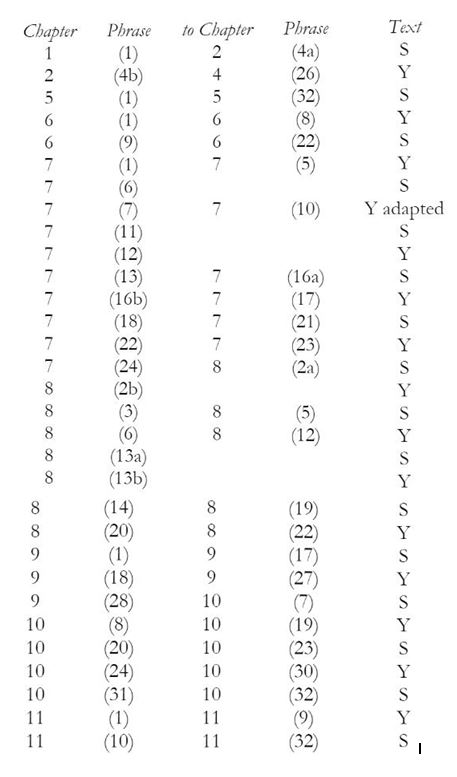

TABLE OF THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE YAHVIST AND

SACERDOTAL TEXTS IN CHAPTERS 1 TO 11 in GENESIS)

The first figure indicates the chapter.

The second figure in brackets indicates the number of phrases, sometimes divided into two parts indicated by the letters a and b.

Letters: Y indicates Yahvist text S indicates Sacerdotal text

Example: The first line of the table indicates: from Chapter 1, phrase 1 to Chapter 2, phrase 4a, the text published in present day Bibles is the Sacerdotal text.

TABLE OF THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE YAHVIST AND

SACERDOTAL TEXTS IN CHAPTERS 1 TO 11 in GENESIS)

What simpler illustration can there be of the way men have manipulated the Biblical Scriptures?

The Book of Samuel and the two Books of Kings are above all biographical collections concerning Samuel, Saul, David, and Solomon. Their historic worth is the subject of debate. From this point of view E. Jacob finds numerous errors in it, because there are sometimes two and even three versions of the same event. The prophets Elias, Elisha and Isaiah also figure here, mixing elements of history and legend. For other commentators, such as Father A. Lefèvre, “the historical value of these books is fundamental.”

Chronicles I & II, the Book of Ezra and the Book of Nehemiah have a single author, called ‘the Chronicler’, writing in the Fourth century B.C. He resumes the whole history of the Creation up to this period, although his genealogical tables only go up to David. In actual fact, he is using above all the Book of Samuel and the Book of Kings, “mechanically copying them out without regard to the inconsistencies” (E. Jacob), but he nevertheless adds precise facts that have been confirmed by archaeology. In these works care is taken to adapt history to the needs of theology. E. Jacob notes that the author “sometimes writes history according to theology”. “To explain the fact that King Manasseh, who was a sacrilegious persecutor, had a long and prosperous reign, he postulates a conversion of the King during a stay in Assyria (Chronicles II, 33/11) although there is no mention of this in any Biblical or non-Biblical source”. The Book of Ezra and the Book of Nehemiah have been severely criticised because they are full of obscure points, and because the period they deal with (the Fourth century B.C.) is itself not very well known, there being few non-Biblical documents from it.

The Books of Tobit, Judith and Esther are classed among the Historical Books. In them very big liberties are taken with history. proper names are changed, characters and events are invented, all for the best of religious reasons. They are in fact stories designed to serve a moral end, pepll)ered with historical improbabilities and inaccuracies.

The Books of Maccabees are of quite a different order. They provide a version of events that took place in the Second century B.C. which is as exact a record of the history of this period as may be found. It is for this reason that they constitute accounts of great value.

The collection of books under the heading ‘historical’ is therefore highly disparate. History is treated in both a scientific and a whimsical fashion.

THE PROPHETIC BOOKS

Under this heading we find the preachings of various prophets who in the Old Testament have been classed separately from the first great prophets such as Moses, Samuel, Elias and Elisha, whose teachings are referred to in other books.

The prophetic books cover the period from the Eighth to the Second century B.C.

In the Eighth century B.C., there were the books of Amos, Hosea, Isaiah and Michah. The first of these is famous for his condemnation of social injustice, the second for his religious corruption which leads him to bodily suffering (for being forced to marry a sacred harlot of a pagan cult), like God suffering for the degradation of His people but still granting them His love. Isaiah is a figure of political history. he is consulted by kings and dominates events; he is the prophet of grandeur. In addition to his personal works, his oracles are published by his disciples right up until the Third century B.C.: protests against iniquities, fear of God’s judgement, proclamations of liberation at the time of exile and later on the return of the Jews to Palestine. It is certain that in the case of the second and third Isaiah, the prophetic intention is paralleled by political considerations that are as clear as daylight. The preaching of Michah, a contemporary of Isaiah, follows the same general ideas.

In the Seventh century B.C., Zephaniah, Jeremiah, Nahum and Habakkuk distinguished themselves by their preachings. Jeremiah became a martyr. His oracles were collected by Baruch who is also perhaps the author of Lamentations.

The period of exile in Babylon at the beginning of the Sixth century B.C. gave birth to intense prophetic activity. Ezekiel figures importantly as the consoler of his brothers, inspiring hope among them. His visions are famous. The Book of Obadiah deals with the misery of a conquered Jerusalem.

After the exile, which came to an end in 538 B.C., prophetic activity resumed with Haggai and Zechariah who urged the reconstruction of the Temple. When it was completed, writings going under the name of Malachi appeared. They contain various oracles of a spiritual nature.

One wonders why the Book of Jonah is included in the prophetic books when the Old Testament does not give it any real text to speak of. Jonah is a story from which one principle fact emerges: the necessary submission to Divine Will.

Daniel was written in three languages (Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek). According to Christian commentators, it is a , disconcerting’ Apocalypse from an historical point of view. It is probably a work from the Maccabaean period, Second century B.C. Its author wished to maintain the faith of his countrymen, at the time of the ‘abomination of desolation’, by convincing them that the moment of deliverance was at hand. (E. Jacob)

THE BOOKS OF POETRY AND WISDOM

These form collections of unquestionable literary unity. Foremost among them are the Psalms, the greatest monument to Hebrew poetry. A large number were composed by David and the others by priests and levites. Their themes are praises, supplications and meditations, and they served a liturgical function.

The book of Job, the book of wisdom and piety par excellence, probably dates from 400-500 B.C.

The author of ‘Lamentations’ on the fall of Jerusalem at the beginning of the Sixth century B.C. may well be Jeremiah.

We must once again mention the Song of Songs, allegorical chants mostly about Divine love, the Book of Proverbs, a collection of the words of Solomon and other wise men of the court, and Ecclesiastes or Koheleth, where earthly happiness and wisdom are debated.

We have, therefore, a collection of works with highly disparate contents written over at least seven centuries, using extremely varied sources before being amalgamated inside a single work.

How was this collection able, over the centuries, to constitute an inseparable whole and-with a few variations according to community-become the book containing the Judeo-Christian Revelation? This book was called in Greek the ‘canon’ because of the idea of intangibility it conveys.

The amalgam does not date from the Christian period, but from Judaism itself, probably with a primary stage in the Seventh century B.C. before later books were added to those already accepted. It is to be noted however that the first five books, forming the Torah or Pentateuch, have always been given pride of place. Once the proclamations of the prophets (the prediction of a chastisement commensurate with misdemeanour) had been fulfilled, there was no difficulty in adding their texts to the books that had already been admitted. The same was true for the assurances of hope given by these prophets. By the Second century B.C., the ‘Canon’ of the prophets had been formed.

Other books, e.g. Psalms, on account of their liturgical function, were integrated along with further writings, such as Lamentations, the Book of Wisdom and the Book of Job.

Christianity, which was initially Judeo-Christianity, has been carefully studied-as we shall see later on-by modern authors, such as Cardinal Daniélou. Before it was transformed under Paul’s influence, Christianity accepted the heritage of the Old Testament without difficulty. The authors of the Gospels adhered very strictly to the latter, but whereas a ‘purge’ has been made of the Gospels by ruling out the ‘Apocrypha’, the same selection has not been deemed necessary for the Old Testament. Everything, or nearly everything, has been accepted.

Who would have dared dispute any aspects of this disparate amalgam before the end of the Middle Ages-in the West at least? The answer is nobody, or almost nobody. From the end of the Middle Ages up to the beginning of modern times, one or two critics began to appear; but, as we have already seen, the Church Authorities have always succeeded in having their own way. Nowadays, there is without doubt a genuine body of textual criticism, but even if ecclesiastic specialists have devoted many of their efforts to examining a multitude of detailed points, they have preferred not to go too deeply into what they euphemistically call difficulties’. They hardly seem disposed to study them in the light of modern knowledge. They may well establish parallels with history-principally when history and Biblical narration appear to be in agreement-but so far they have not committed themselves to be a frank and thorough comparison with scientific ideas. They realize that this would lead people to contest notions about the truth of Judeo-Christian Scriptures, which have so far remained undisputed.

The Old Testament and Science Findings

Few of the subjects dealt within the Old Testament, and likewise the Gospels, give rise to a confrontation with the data of modern knowledge. When an incompatibility does occur between the Biblical text and science, however, it is on extremely important points.

As we have already seen in the preceding chapter, historical errors were found in the Bible and we have quoted several of these pinpointed by Jewish and Christian experts in exegesis. The latter have naturally had a tendency to minimize the importance of such errors. They find it quite natural for a sacred author to present historical fact in accordance with theology and to write history to suit certain needs. We shall see further on, in the case of the Gospel according to Matthew, the same liberties taken with reality and the same commentaries aimed at making admissible as reality what is in contradiction to it. A logical and objective mind cannot be content with this procedure.

From a logical angle, it is possible to single out a large number of contradictions and improbabilities. The existence of different sources that might have been used in the writing of a description may be at the origin of two different presentations of the same fact. This is not all; different adaptations, later additions to the text itself, like the commentaries added a posteriori, then included in the text later on when a new copy was made-these are perfectly recognized by specialists in textual criticism and very frankly underlined by some of them. In the case of the Pentateuch alone, for example, Father de Vaux in the General Introduction preceding his translation of Genesis (pages 13 and 14), has drawn attention to numerous disagreements. We shall not quote them here since we shall be quoting several of them later on in this study. The general impression one gains is that one must not follow the text to the letter.

Here is a very typical example:

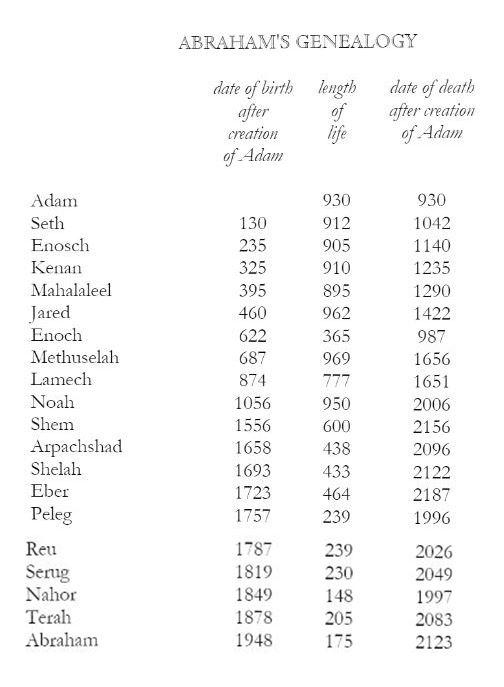

In Genesis (6, 3), God decides just before the Flood henceforth to limit man’s lifespan to one hundred and twenty years, “… his days shall be a hundred and twenty years”. Further on however, we note in Genesis (11, 10-32) that the ten descendants of Noah had lifespans that range from 148 to 600 years (see table in this chapter showing Noah’s descendants down to Abraham). The contradiction between these two passages is quite obvious. The explanation is elementary. The first passage (Genesis 6, 3) is a Yahvist text, probably dating as we have already seen from the Tenth century B.C. The second passage in Genesis (11, 10-32) is a much more recent text (Sixth century B.C.) from the Sacerdotal version. This version is at the origin of these genealogies, which are as precise in their information on lifespans as they are improbable when taken en masse.

It is in Genesis that we find the most evident incompatibilities with modern science. These concern three essential points:

1) the Creation of the world and its stages;

2) the date of the Creation of the world and the date of man’s appearance on earth;

3) the description of the Flood.

THE CREATION OF THE WORLD

As Father de Vaux points out, Genesis “starts with two juxtaposed descriptions of the Creation”. When examining them from the point of view of their compatibility with modern scientific data, we must look at each one separately.

First Description of the Creation

The first description occupies the first chapter and the very first verses of the second chapter. It is a masterpiece of inaccuracy from a scientific point of view. It must be examined one paragraph at a time. The text reproduced here is from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible.[11]

Chapter 1, verses 1 & 2:

“In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the Spirit of God was moving over the face of the waters.”

It is quite possible to admit that before the Creation of the Earth, what was to become the Universe as we know it was covered in darkness. To mention the existence of water at this period is however quite simply pure imagination. We shall see in the third part of this book how there is every indication that at the initial stage of the formation of the universe a gaseous mass existed. It is an error to place water in it.

Verses 3 to 5:

“And God said, ‘Let there be light’, and there was light. And God saw that the light was good; and God separated the light from the darkness. God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And there was evening and there was morning, one day.”

The light circulating in the Universe is the result of complex reactions in the stars. We shall come back to them in the third part of this work. At this stage in the Creation, however, according to the Bible, the stars were not yet formed. The “lights’ of the firmament are not mentioned in Genesis until verse 14, when they were created on the Fourth day, “to separate the day from the night”, “to give light upon earth”; all of which is accurate. It is illogical, however, to mention the result (light) on the first day, when the cause of this light was created three days later. The fact that the existence of evening and morning is placed on the first day is moreover, purely imaginary; the existence of evening and morning as elements of a single day is only conceivable after the creation of the earth and its rotation under the light of its own star, the Sun!

-verses 6 to 8:

“And God said, “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.’ And God made the firmament and separated the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament. And it was so. And God called the firmament Heaven. And there was evening and there was morning, a second day.”

The myth of the waters is continued here with their separation into two layers by a firmament that in the description of the Flood allows the waters above to pass through and flow onto the earth. This image of the division of the waters into two masses is scientifically unacceptable.

-verses 9 to 13:

“And God said, “Let the waters under the heavens be gathered together into one place, and let the dry land appear.’ And it was so. God called the dry land Earth, and the waters that were gathered together he called Seas. And God saw that it was good. And God said, “Let the earth put forth vegetation, plants yielding seed, and fruit trees bearing fruit in which is their seed, each according to its kind upon the earth.’ And it was so. The earth brought forth vegetation, plants yielding seed according to their own kinds, and trees bearing fruit in which is their seed, each according to its kind. And God saw that it was good. And there was evening and there was morning, a third day.”

The fact that continents emerged at the period in the earth’s history, when it was still covered with water, is quite acceptable scientifically. What is totally untenable is that a highly organized vegetable kingdom with reproduction by seed could have appeared before the existence of the sun (in Genesis it does not appear until the fourth day), and likewise the establishment of alternating nights and days.

-verses 14 to 19:

“And God said, ‘Let there be lights in the firmaments of the heavens to separate the day from night; and let them be for signs and for seasons and for days and years, and let them be lights in the firmament of the heavens to give light upon the earth.’ And it was so. And God made the two great lights, the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night; he made the stars also. And God set them in the firmament of the heavens to give light upon earth, to rule over. the day and over the night, and to separate the light from the darkness. And God saw that it was good. And there was evening and there was morning, a fourth day.”

Here the Biblical author’s description is acceptable. The only criticism one could level at this passage is the position it occupies in the description as a whole. Earth and Moon emanated, as we know, from their original star, the Sun. To place the creation of the Sun and Moon after the creation of the Earth is contrary to the most firmly established ideas on the formation of the elements of the Solar System.

-verses 20 to 30:

“And God said, “Let the waters bring forth swarms of living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the firmament of the heavens.’ So God created the great sea monsters and every living creature that moves, with which the waters swarm, according to their kinds, and every winged bird according to its kind. And God saw that it was good. And God blessed them saying, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the waters in the seas, and let birds multiply on the earth.’ And there was evening and there was morning, a fifth day.”

This passage contains assertions which are unacceptable.

According to Genesis, the animal kingdom began with the appearance of creatures of the sea and winged birds. The Biblical description informs us that it was not until the next day-as we shall see in the following verses-that the earth itself was populated by animals.

It is certain that the origins of life came from the sea, but this question will not be dealt with until the third part of this book. From the sea, the earth was colonized, as it were, by the animal kingdom. It is from animals living on the surface of the earth, and in particular from one species of reptile which lived in the Second era, that it is thought the birds originated. Numerous biological characteristics common to both species make this deduction possible. The beasts of the earth are not however mentioned until the sixth day in Genesis; after the appearance of the birds. This order of appearance, beasts of the earth after birds, is not therefore acceptable.

-verses 24 to 31:

“And God said, “Let the earth bring forth living creatures according to their kinds: cattle and creeping things and beasts of the earth according to their kinds.’ And it was so. And God made the beasts of the earth according to their kinds and the cattle according to their kinds, and everything that creeps upon the ground according to its kind. And God saw that it was good.”

“Then God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness; and let them have dominion (sic) over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth”.

“So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.”

“And God blessed them, and God said to them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.’ And God said, “Behold, I have given you every plant yielding seed which is upon the face of the earth, and every tree with seed in its fruit; you shall have them for food. And to every beast of the earth, and to every bird of the air, and to everything that creeps on the earth, everything that has the breath of life, I have given every green plant for food.” And it was so. And God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good. And there was evening and there was morning, a sixth day.”

This is the description of the culmination of the Creation. The author lists all the living creatures not mentioned before and describes the various kinds of food for man and beast.

As we have seen, the error was to place the appearance of beasts of the earth after that of the birds. Man’s appearance is however correctly situated after the other species of living things.

The description of the Creation finishes in the first three verses of Chapter 2:

“Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all the host (sic) of them. And on the seventh day God finished his work which he had done, and he rested on the seventh day from all his work which he had done. So God blessed the seventh day and hallowed it, because on it God rested from all his work which he had done in creation;

These are the generations of the heavens and the earth when they were created.”

This description of the seventh day calls for some comment.

Firstly the meaning of certain words. The text is taken from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible mentioned above. The word ‘host’ signifies here, in all probability, the multitude of beings created. As for the expression ‘he rested’, it is a manner of translating the Hebrew word ‘shabbath’, from which the Jewish day for rest is derived, hence the expression in English ‘sabbath’.

It is quite clear that the ‘rest’ that God is said to have taken after his six days’ work is a legend. There is nevertheless an explanation for this. We must bear in mind that the description of the creation examined here is taken from the so-called Sacerdotal version, written by priests and scribes who were the spiritual successors of Ezekiel, the prophet of the exile to Babylon writing in the Sixth century B.C. We have already seen how the priests took the Yahvist and Elohist versions of Genesis and remodelled them after their own fashion in accordance with their own preoccupations. Father de Vaux has written that the ‘legalist’ character of these writings was very essential. An outline of this has already been given above.

Whereas the Yahvist text of the Creation, written several centuries before the Sacerdotal text, makes no mention of God’s sabbath, taken after the fatigue of a week’s labor, the authors of the Sacerdotal text bring it into their description. They divide the latter into separate days, with the very precise indication of the days of the week. They build it around the sabbatic day of rest which they have to justify to the faithful by pointing out that God was the first to respect it. Subsequent to this practical necessity, the description that follows has an apparently logical religious order, but in fact scientific data permit us to qualify the latter as being of a whimsical nature.

The idea that successive phases of the Creation, as seen by the Sacerdotal authors in their desire to incite people to religious observation, could have been compressed into the space of one week is one that cannot be defended from a scientific point of view. Today we are perfectly aware that the formation of the Universe and the Earth took place in stages that lasted for very long periods. (In the third part of the present work, we shall examine this question when we come to look at the Qur’anic data concerning the Creation). Even if the description came to a close on the evening of the sixth day, without mentioning the seventh day, the ‘sabbath’ when God is said to have rested, and even if, as in the Qur’anic description, we were permitted to think that they were in fact undefined periods rather than actual days, the Sacerdotal description would still not be any more acceptable. The succession of episodes it contains is an absolute contradiction with elementary scientific knowledge.

It may be seen therefore that the Sacerdotal description of the Creation stands out as an imaginative and ingenious fabrication. Its purpose was quite different from that of making the truth known.

Second Description

The second description of the Creation in Genesis follows immediately upon the first without comment or transitional passage. It does not provoke the same objections.

We must remember that this description is roughly three centuries older and is very short. It allows more space to the creation of man and earthly paradise than to the creation of the Earth and Heavens. It mentions this very briefly

(Chapter2, 4b-7): “In the day that Yahweh God made the earth and the heavens, when no plant of the field was yet in the earth and no herb of the field had yet sprung up-for Yahweh God had not caused it to rain upon the earth, and there was no man to till the ground;

but a flood went up from earth and watered the whole face of the ground-then Yahweh God formed man of dust from the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living being.”

This is the Yahvist text that appears in the text of present day Bibles. The Sacerdotal text was added to it later on, but one may ask if it was originally so brief. Nobody is in a position to say whether the Yahvist text has not, in the course of time, been pared down. We do not know if the few lines we possess represent all that the oldest Biblical text of the Creation had to say.