Sources Of The Gospels

The latest studies in textual criticism on the sources of the Gospels have clearly shown an even more complicated formation process of the texts.

The general outline that has been given here of the Gospels and which emerges from a critical examination of the texts tends to make one think of literature that is “disjointed, with a plan that lacks continuity” and “seemingly insuperable contradictions”. These are the terms used in the judgement passed on them by the commentators of the Ecumenical Translation of the Bible. It is important to refer to their authority because the consequences of an appraisal of this subject are extremely serious. It has already been seen how a few notions concerning the religious history of the time when the Gospels were written helped to explain certain disconcerting aspects of this literature appears to the thoughtful reader. It is necessary to continue, however, and ascertain what present-day works can tell us about the sources the Evangelists drew on when writing their texts. It is also interesting to see whether the history of the texts, once they were established, can help to explain certain aspects they present today.

The problem of sources was approached in a very simplistic fashion at the time of the Fathers of the Church. In the early centuries of Christianity, the only source available was the Gospel that the complete manuscripts provided first, i.e. Matthew’s Gospel. The problem of sources only concerned Mark and Luke because John constituted a quite separate case. Saint Augustine held that Mark, who appears second in the traditional order of presentation, had been inspired by Matthew and had summarized his work. He further considered that Luke, who comes third in the manuscripts, had used data from both; his prologue suggests this and has already been discussed.

The experts in exegesis at this period were as able as we are to estimate the degree of corroboration between the texts and find a large number of verses common to two or three synoptics. Today, the commentators of the Ecumenical Translation of the Bible provide the following figures:

verses common to all three synoptics ————– 330

verses common to Mark and Matthew ———— 178

verses common to Mark and Luke —————-100

verses common to Matthew and Luke ———— 230

The verses unique to each of the first three Gospels are as follows: Matthew 330, Mark 53, and Luke 500.

Church Window

From the Fathers of the Church until the end of the Eighteenth century A.D., one and a half millenia passed without any new problems being raised on the sources of the evangelists: people continued to follow tradition. It was not until modem times that it was realized, on the basis of these data, how each evangelist had taken material found in the others and compiled his own specific narration guided by his own personal views. A great weight was attached to the actual collection of material for the narration. It came from the oral traditions of the communities from which it originated on the one hand, and from a common written Aramaic source that has not been rediscovered on the other. This written source could have formed a compact mass or have been composed of many fragments of different narrations used by each evangelist to construct his own original work.

More intensive studies in circa the last hundred years have led to theories that are more detailed and in time will become even more complicated. The first of the modem theories is the so-called ‘Holtzmann Two Sources Theory’, (1863). O. Culmann and the Ecumenical Translation explain that, according to this theory, Matthew and Luke may have been inspired by Mark on the one hand and on the other by a common document that has since been lost. The first two moreover each had his own sources. This leads to the following diagram:

SOURCES OF THE GOSPELS

Culmann criticises the above on the following points:

- Mark’s work, used by both Luke and Matthew, was probably not the author’s Gospel but an earlier version.

- The diagram does not lay enough emphasis on the oral tradition. This appears to be of paramount importance because it alone preserved Jesus’s words and the descriptions of his mission during a period of thirty or forty years, as each of the Evangelists was only the spokesman for the Christian community which wrote down the oral tradition.

This is how it is possible to conclude that the Gospels we possess today are a reflection of what the early Christian communities knew of Jesus’s life and ministry. They also mirror their beliefs and theological ideas, of which the evangelists were the spokesmen.

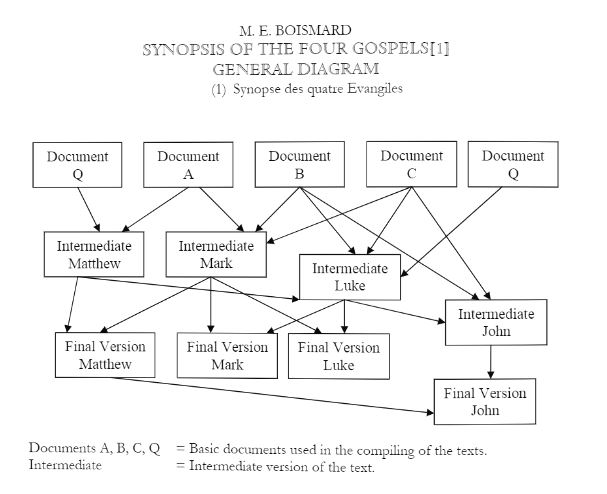

The latest studies in textual criticism on the sources of the Gospels have clearly shown an even more complicated formation process of the texts. A book by Fathers Benoit and Boismard, both professors at the Biblical School of Jerusalem (1972-1973), called the Synopsis of the Four Gospels (Synopse des quatres Evangiles) stresses the evolution of the text in stages parallel to the evolution of the tradition. This implies the conquences set out by Father Benoit in his introduction to Father Boismard’s part of the work. He presents them in the following terms:

“(. . .) the wording and form of description that result from a long evolution of tradition are not as authentic as in the original. some readers of this work will perhaps be surprised or embarrassed to learn that certain of Jesus’s sayings, parables, or predictions of His destiny were not expressed in the way we read them today, but were altered and adapted by those who transmitted them to us. This may come as a source of amazement and even scandal to those not used to this kind of historical investigation.”

The alterations and adaptations to the texts made by those transmitting them to us were done in a way that Father Boismard explains by means of a highly complex diagram. It is a development of the so-called ‘Two Sources Theory’, and is the product of examination and comparison of the texts which it is not possible to summarize here. Those readers who are interested in obtaining further details should consult the original work published by Les Editions du Cerf, Paris.

Four basic documents-A, B, C and Q-represent the original sources of the Gospels (see general diagram). Page 76.

Document A comes from a Judeo-Christian source. Matthew and Mark were inspired by it.

Document B is a reinterpretation of document A, for use in Pagan-cum-Christian churches: all the evangelists were inspired by it except Matthew.

Document C inspired Mark, Luke and John.

Document Q constitutes the majority of sources common to Matthew and Luke; it is the , Common Document’ in the ‘Two Sources’ theory referred to earlier.

None of these basic documents led to the production of the definitive texts we know today. Between them and the final version lay the intermediate versions: Intermediate Matthew, Intermediate Mark, Intermediate Luke and Intermediate John. These four intermediate documents were to lead to the final versions of the four Gospels, as well as to inspire the final corresponding versions of other Gospels. One only has to consult the diagram to see the intricate relationships the author has revealed.

The results of this scriptural research are of great importance. They show how the Gospel texts not only have a history (to be discussed later) but also a ‘pre-history’, to use Father Boismard’s expression. What is meant is that before the final versions appeared, they underwent alterations at the Intermediate Document stage. Thus it is possible to explain, for example, how a well-known story from Jesus’s life, such as the miracle catch of fish, is shown in Luke to be an event that happened during His life, and in John to be one of His appearances after His Resurrection.

The conclusion to be drawn from the above is that when we read the Gospel, we can no longer be at all sure that we are reading Jesus’s word. Father Benoit addresses himself to the readers of the Gospel by warning them and giving them the following compensation: “If the reader is obliged in more than one case to give up the notion of hearing Jesus’s voice directly, he still hears the voice of the Church and he relies upon it as the divinely appointed interpreter of the Master who long ago spoke to us on earth and who now speaks to us in His glory”.

How can one reconcile this formal statement of the inauthenticity of certain texts with the phrase used in the dogmatic constitution on Divine Revelation by the Second Vatican Council assuring us to the contrary, i.e. the faithful transmission of Jesus’s words: “These four Gospels, which it (the Church) unhesitatingly confirms are historically authentic, faithfully transmit what Jesus, Son of God, actually did and taught during his life among men for their eternal salvation, until the day when he was taken up into the heavens”?

It is quite clear that the work of the Biblical School of Jerusalem flatly contradicts the Council’s declaration.

SYNOPSIS OF THE FOUR GOSPELS

GENERAL DIAGRAM

By Dr. Maurice Bucaille

This article is borrowed from The Bible, The Qur’an and Science