What Is Conscience?

Page Contents

Conscience is a cognitive process that elicits emotion and rational associations based on an individual’s moral philosophy or value system. Conscience stands in contrast to elicited emotion or thought due to associations based on immediate sensory perceptions and reflexive responses, as in sympathetic central nervous system responses. In common terms, conscience is often described as leading to feelings of remorse when a person commits an act that conflicts with their moral values. An individual’s moral values and their dissonance with familial, social, cultural and historical interpretations of moral philosophy are considered in the examination of cultural relativity in both the practice and study of psychology. The extent to which conscience informs moral judgment before an action and whether such moral judgments are or should be based on reason has occasioned debate through much of modern history between theories of modern western philosophy in juxtaposition to the theories of romanticism and other reactionary movements after the end of the Middle Ages

Religious views of conscience usually see it as linked to a morality inherent in all humans, to a beneficent universe and/or to divinity. The diverse ritualistic, mythical, doctrinal, legal, institutional and material features of religion may not necessarily cohere with experiential, emotive, spiritual or contemplative considerations about the origin and operation of conscience. Common secular or scientific views regard the capacity for conscience as probably genetically determined, with its subject probably learned or imprinted as part of a culture.

Commonly used metaphors for conscience include the “voice within”, the “inner light”, or even Socrates’ reliance on what the Greeks called his “daimōnic sign”, an averting (ἀποτρεπτικός apotreptikos) inner voice heard only when he was about to make a mistake. Conscience, as is detailed in sections below, is a concept in national and international law, is increasingly conceived of as applying to the world as a whole, has motivated numerous notable acts for the public good and been the subject of many prominent examples of literature, music and film.

Responsibilities

Views

Further information: Origins of morality and Morality

Although humanity has no generally accepted definition of conscience or universal agreement about its role in ethical decision-making, three approaches have addressed it:

- Religious views

- Secular views

- Philosophical views

Religious

Further information: Religious belief, Philosophy of religion, and Spirituality

In the literary traditions of the Upanishads, Brahma Sutras and the Bhagavad Gita, conscience is the label given to attributes composing knowledge about good and evil, that a soul acquires from the completion of acts and consequent accretion of karma over many lifetimes. According to Adi Shankara in his Vivekachudamani morally right action (characterised as humbly and compassionately performing the primary duty of good to others without expectation of material or spiritual reward), helps “purify the heart” and provide mental tranquility but it alone does not give us “direct perception of the Reality”. This knowledge requires discrimination between the eternal and non-eternal and eventually a realization in contemplation that the true self merges in a universe of pure consciousness.

In the Zoroastrian faith, after death a soul must face judgment at the Bridge of the Separator; there, evil people are tormented by prior denial of their own higher nature, or conscience, and “to all time will they be guests for the House of the Lie.” The Chinese concept of Ren, indicates that conscience, along with social etiquette and correct relationships, assist humans to follow The Way (Tao) a mode of life reflecting the implicit human capacity for goodness and harmony.

Conscience also features prominently in Buddhism. In the Pali scriptures, for example, Buddha links the positive aspect of conscience to a pure heart and a calm, well-directed mind. It is regarded as a spiritual power, and one of the “Guardians of the World”. The Buddha also associated conscience with compassion for those who must endure cravings and suffering in the world until right conduct culminates in right mindfulness and right contemplation. Santideva (685–763 CE) wrote in the Bodhicaryavatara (which he composed and delivered in the great northern Indian Buddhist university of Nalanda) of the spiritual importance of perfecting virtues such as generosity, forbearance and training the awareness to be like a “block of wood” when attracted by vices such as pride or lust; so one can continue advancing towards right understanding in meditative absorption. Conscience thus manifests in Buddhism as unselfish love for all living beings which gradually intensifies and awakens to a purer awareness where the mind withdraws from sensory interests and becomes aware of itself as a single whole.

The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote in his Meditations that conscience was the human capacity to live by rational principles that were congruent with the true, tranquil and harmonious nature of our mind and thereby that of the Universe: “To move from one unselfish action to another with God in mind. Only there, delight and stillness … the only rewards of our existence here are an unstained character and unselfish acts.”

Taqwa

Main articles: Taqwa and Taqwa (Piety)

Last page of Ghazali’s autobiography in MS Istanbul, Shehid Ali Pasha 1712, dated A.H. 509 = 1115–1116. Ghazali’s crisis of epistemological skepticism was resolved by “a light which God Most High cast into my breast … the key to most knowledge.”

The Islamic concept of Taqwa is closely related to conscience. In the Qur’ān verses 2:197 & 22:37 Taqwa refers to “right conduct” or “piety”, “guarding of oneself” or “guarding against evil”. Qur’ān verse 47:17 says that God is the ultimate source of the believer’s taqwā which is not simply the product of individual will but requires inspiration from God. In Qur’ānverses 91:7–8, God the Almighty talks about how He has perfected the soul, the conscience and has taught it the wrong (fujūr) and right (taqwā). Hence, the awareness of vice and virtue is inherent in the soul, allowing it to be tested fairly in the life of this world and tried, held accountable on the day of judgment for responsibilities to God and all humans.

Qur’ān verse 49:13 states:

“O humankind! We have created you out of male and female and constituted you into different groups and societies, so that you may come to know each other-the noblest of you, in the sight of God, are the ones possessing taqwā.”

In Islam, according to eminent theologians such as Al-Ghazali, although events are ordained (and written by God in al-Lawh al-Mahfūz, the Preserved Tablet), humans possess free will to choose between wrong and right, and are thus responsible for their actions; the conscience being a dynamic personal connection to God enhanced by knowledge and practise of the Five Pillars of Islam, deeds of piety, repentance, self-discipline and prayer; and disintegrated and metaphorically covered in blackness through sinful acts.Marshall Hodgson wrote the three-volume work: The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization.

In the Protestant Christian tradition, Martin Luther insisted in the Diet of Worms that his conscience was captive to the Word of God, and it was neither safe nor right to go against conscience. To Luther, conscience falls within the ethical, rather than the religious, sphere. John Calvin saw conscience as a battleground: “[…] the enemies who rise up in our conscience against his Kingdom and hinder his decrees prove that God’s throne is not firmly established therein”. Many Christians regard following one’s conscience as important as, or even more important than, obeying human authority. A fundamentalist Christian view of conscience might be: ‘God gave us our conscience so we would know when we break His Law; the guilt we feel when we do something wrong tells us that we need to repent.’ This can sometimes (as with the conflict between William Tyndale and Thomas More over the translation of the Bible into English) lead to moral quandaries: “Do I unreservedly obey my Church/priest/military/political leader or do I follow my own inner feeling of right and wrong as instructed by prayer and a personal reading of scripture?” Some contemporary Christian churches and religious groups hold the moral teachings of the Ten Commandments or of Jesus as the highest authority in any situation, regardless of the extent to which it involves responsibilities in law. In the Gospel of John (7:53–8:11) (King James Version) Jesus challenges those accusing a woman of adultery stating: “‘He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.’ And again he stooped down, and wrote on the ground. And they which heard it, being convicted by their own conscience, went out one by one” (see Jesus and the woman taken in adultery). In the Gospel of Luke (10: 25–37) Jesus tells the story of how a despised and heretical Samaritan (see Parable of the Good Samaritan) who (out of compassion and conscience) helps an injured stranger beside a road, qualifies better for eternal life by loving his neighbor, than a priest who passes by on the other side.

This dilemma of obedience in conscience to divine or state law, was demonstrated dramatically in Antigone’s defiance of King Creon’s order against burying her brother an alleged traitor, appealing to the “unwritten law” and to a “longer allegiance to the dead than to the living”.

Catholic theology sees conscience as the last practical “judgment of reason which at the appropriate moment enjoins [a person] to do good and to avoid evil”. The Second Vatican Council (1962–65) describes: “Deep within his conscience man discovers a law which he has not laid upon himself but which he must obey. Its voice, ever calling him to love and to do what is good and to avoid evil, tells him inwardly at the right movement: do this, shun that. For man has in his heart a law inscribed by God. His dignity lies in observing this law, and by it he will be judged. His conscience is man’s most secret core, and his sanctuary. There he is alone with God whose voice echoes in his depths.” Thus, conscience is not like the will, nor a habit like prudence, but “the interior space in which we can listen to and hear the truth, the good, the voice of God. It is the inner place of our relationship with Him, who speaks to our heart and helps us to discern, to understand the path we ought to take, and once the decision is made, to move forward, to remain faithful” In terms of logic, conscience can be viewed as the practical conclusion of a moral syllogism whose major premise is an objective norm and whose minor premise is a particular case or situation to which the norm is applied. Thus, Catholics are taught to carefully educate themselves as to revealed norms and norms derived therefrom, so as to form a correct conscience. Catholics are also to examine their conscience daily and with special care before confession. Catholic teaching holds that, “Man has the right to act according to his conscience and in freedom so as personally to make moral decisions. He must not be forced to act contrary to his conscience. Nor must he be prevented from acting according to his conscience, especially in religious matters”. This right of conscience does not allow one to arbitrarily disagree with Church teaching and claim that one is acting in accordance with conscience. A sincere conscience presumes one is diligently seeking moral truth from authentic sources, that is, seeking to conform oneself to that moral truth by listening to the authority established by Christ to teach it. Nevertheless, despite one’s best effort, “[i]t can happen that moral conscience remains in ignorance and makes erroneous judgments about acts to be performed or already committed … This ignorance can often be imputed to personal responsibility … In such cases, the person is culpable for the wrong he commits.” Thus, if one realizes one may have made a mistaken judgment, one’s conscience is said to be vincibly erroneous and it is not a valid norm for action. One must first remove the source of error and do one’s best to achieve a correct judgment. If, however, one is not aware of one’s error or if, despite an honest and diligent effort one cannot remove the error by study or seeking advice, then one’s conscience may be said to be invincibly erroneous. It binds since one has subjective certainty that one is correct. The act resulting from acting on the invincibly erroneous conscience is not good in itself, yet this deformed act or material sin against God’s right order and the objective norm is not imputed to the person. The formal obedience given to such a judgment of conscience is good. Some Catholics appeal to conscience in order to justify dissent, not on the level of conscience properly understood, but on the level of the principles and norms which are supposed to inform conscience. For example, some priests make on the use of the so-called internal forum solution (which is not sanctioned by the Magisterium) to justify actions or lifestyles incompatible with Church teaching, such as Christ’s prohibition of remarriage after divorce or sexual activity outside marriage. The Catholic Church has warned that “rejection of the Church’s authority and her teaching … can be at the source of errors in judgment in moral conduct”. An example of someone following his conscience to the point of accepting the consequence of being condemned to death is Sir Thomas More (1478-1535). A theologian who wrote on the distinction between the ‘sense of duty’ and the ‘moral sense’, as two aspects of conscience, and who saw the former as some feeling that can only be explained by a divine Lawgiver, was John Henry Cardinal Newman. A well known saying of him is that he would first toast on his conscience and only then on the pope, since his conscience brought him to acknowledge the authority of the pope.

Judaism arguably does not require uncompromising obedience to religious authority; the case has been made that throughout Jewish history rabbis have circumvented laws they found unconscionable, such as capital punishment. Similarly, although an occupation with national destiny has been central to the Jewish faith (see Zionism) many scholars (including Moses Mendelssohn) stated that conscience as a personal revelation of scriptural truth was an important adjunct to the Talmudic tradition. The concept of inner light in the Religious Society of Friends or Quakers is associated with conscience. Freemasonry describes itself as providing an adjunct to religion and key symbols found in a Freemason Lodge are the square and compasses explained as providing lessons that Masons should “square their actions by the square of conscience”, learn to “circumscribe their desires and keep their passions within due bounds toward all mankind.” The historian Manning Clark viewed conscience as one of the comforters that religion placed between man and death but also a crucial part of the quest for grace encouraged by the Book of Job and the Book of Ecclesiastes, leading us to be paradoxically closest to the truth when we suspect that what matters most in life (“being there when everyone suddenly understands what it has all been for”) can never happen. Leo Tolstoy, after a decade studying the issue (1877–1887), held that the only power capable of resisting the evil associated with materialism and the drive for social power of religious institutions, was the capacity of humans to reach an individual spiritual truth through reason and conscience. Many prominent religious works about conscience also have a significant philosophical component: examples are the works of Al-Ghazali, Avicenna, Aquinas, Joseph Butler and Dietrich Bonhoeffer (all discussed in the philosophical views section).

Secular

The secular approach to conscience includes psychological, physiological, sociological, humanitarian, and authoritarian views. Lawrence Kohlberg considered critical conscience to be an important psychological stage in the proper moral development of humans, associated with the capacity to rationally weigh principles of responsibility, being best encouraged in the very young by linkage with humorous personifications (such as Jiminy Cricket) and later in adolescents by debates about individually pertinent moral dilemmas. Erik Erikson placed the development of conscience in the ‘pre-schooler’ phase of his eight stages of normal human personality development. The psychologist Martha Stout terms conscience “an intervening sense of obligation based in our emotional attachments.” Thus a good conscience is associated with feelings of integrity, psychological wholeness and peacefulness and is often described using adjectives such as “quiet”, “clear” and “easy”.

Sigmund Freud regarded conscience as originating psychologically from the growth of civilisation, which periodically frustrated the external expression of aggression: this destructive impulse being forced to seek an alternative, healthy outlet, directed its energy as a superego against the person’s own “ego” or selfishness (often taking its cue in this regard from parents during childhood). According to Freud, the consequence of not obeying our conscience is guilt, which can be a factor in the development of neurosis; Freud claimed that both the cultural and individual super-ego set up strict ideal demands with regard to the moral aspects of certain decisions, disobedience to which provokes a ‘fear of conscience’.

Antonio Damasio considers conscience an aspect of extended consciousness beyond survival-related dispositions and incorporating the search for truth and desire to build norms and ideals for behavior.

Conscience as a society-forming instinct

Michel Glautier argues that conscience is one of the instincts and drives which enable people to form societies: groups of humans without these drives or in whom they are insufficient cannot form societies and do not reproduce their kind as successfully as those that do.

Charles Darwin considered that conscience evolved in humans to resolve conflicts between competing natural impulses-some about self-preservation but others about safety of a family or community; the claim of conscience to moral authority emerged from the “greater duration of impression of social instincts” in the struggle for survival. In such a view, behavior destructive to a person’s society (either to its structures or to the persons it comprises) is bad or “evil”. Thus, conscience can be viewed as an outcome of those biological drives that prompt humans to avoid provoking fear or contempt in others; being experienced as guilt and shame in differing ways from society to society and person to person. A requirement of conscience in this view is the capacity to see ourselves from the point of view of another person. Persons unable to do this (psychopaths, sociopaths, narcissists) therefore often act in ways which are “evil”.

Fundamental in this view of conscience is that humans consider some “other” as being in a social relationship. Thus, nationalism is invoked in conscience to quell tribal conflict and the notion of a Brotherhood of Man is invoked to quell national conflicts. Yet such crowd drives may not only overwhelm but redefine individual conscience. Friedrich Nietzsche stated: “communal solidarity is annihilated by the highest and strongest drives that, when they break out passionately, whip the individual far past the average low level of the ‘herd-conscience.’ Jeremy Bentham noted that: “fanaticism never sleeps … it is never stopped by conscience; for it has pressed conscience into its service.” Hannah Arendt in her study of the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem, notes that the accused, as with almost all his fellow Germans, had lost track of his conscience to the point where they hardly remembered it; this wasn’t caused by familiarity with atrocities or by psychologically redirecting any resultant natural pity to themselves for having to bear such an unpleasant duty, so much as by the fact that anyone whose conscience did develop doubts could see no one who shared them: “Eichmann did not need to close his ears to the voice of conscience … not because he had none, but because his conscience spoke with a “respectable voice”, with the voice of the respectable society around him”.

Sir Arthur Keith in 1948 developed the Amity-enmity complex. We evolved as tribal groups surrounded by enemies; thus conscience evolved a dual role; the duty to save and protect members of the in-group, and the duty to show hatred and aggression towards any out-group.

An interesting area of research in this context concerns the similarities between our relationships and those of animals, whether animals in human society (pets, working animals, even animals grown for food) or in the wild. One idea is that as people or animals perceive a social relationship as important to preserve, their conscience begins to respect that former “other”, and urge actions that protect it. Similarly, in complex territorial and cooperative breeding bird communities (such as the Australian magpie) that have a high degree of etiquettes, rules, hierarchies, play, songs and negotiations, rule-breaking seems tolerated on occasions not obviously related to survival of the individual or group; behaviour often appearing to exhibit a touching gentleness and tenderness.

Evolutionary biology

Contemporary scientists in evolutionary biology seek to explain conscience as a function of the brain that evolved to facilitate altruism within societies. In his book The God Delusion, Richard Dawkins states that he agrees with Robert Hinde’s Why Good is Good, Michael Shermer’s The Science of Good and Evil, Robert Buckman’s Can We Be Good Without God? and Marc Hauser’s Moral Minds, that our sense of right and wrong can be derived from our Darwinian past. He subsequently reinforced this idea through the lense of the gene-centered view of evolution, since the unit of natural selection is neither an individual organism nor a group, but rather the “selfish” gene, and these genes could ensure their own “selfish” survival by, inter alia, pushing individuals to act altruistically towards its kin.

Neuroscience and artificial conscience

Numerous case studies of brain damage have shown that damage to areas of the brain (such as the anterior prefrontal cortex) results in the reduction or elimination of inhibitions, with a corresponding radical change in behaviour. When the damage occurs to adults, they may still be able to perform moral reasoning; but when it occurs to children, they may never develop that ability.

Attempts have been made by neuroscientists to locate the free will necessary for what is termed the ‘veto’ of conscience over unconscious mental processes (see Neuroscience of free will and Benjamin Libet) in a scientifically measurable awareness of an intention to carry out an act occurring 350–400 microseconds after the electrical discharge known as the ‘readiness potential.’

Jacques Pitrat claims that some kind of artificial conscience is beneficial in artificial intelligence systems to improve their long-term performance and direct their introspective processing.

Philosophical

Further information: Free will, Compatibilism, incompatibilism, Determinism, Libertarianism (metaphysics), Virtue ethics

The word “conscience” derives etymologically from the Latin conscientia, meaning “privity of knowledge” or “with-knowledge”. The English word implies internal awareness of a moral standard in the mind concerning the quality of one’s motives, as well as a consciousness of our own actions. Thus conscience considered philosophically may be first, and perhaps most commonly, a largely unexamined “gut feeling” or “vague sense of guilt” about what ought to be or should have been done. Conscience in this sense is not necessarily the product of a process of rational consideration of the moral features of a situation (or the applicable normative principles, rules or laws) and can arise from parental, peer group, religious, state or corporate indoctrination, which may or may not be presently consciously acceptable to the person (“traditional conscience”).Conscience may be defined as the practical reason employed when applying moral convictions to a situation (“critical conscience”). In purportedly morally mature mystical people who have developed this capacity through daily contemplation or meditation combined with selfless service to others, critical conscience can be aided by a “spark” of intuitive insight or revelation (called marifa in Islamic Sufi philosophy and synderesis in medieval Christian scholastic moral philosophy). Conscience is accompanied in each case by an internal awareness of ‘inner light’ and approbation or ‘inner darkness’ and condemnation as well as a resulting conviction of right or duty either followed or declined.

Medieval

The medieval Persian philosopher Ibn Sina( Avicenna) developed a sensory deprivation thought experiment to explore the relationship between conscience and God

The medieval Islamic scholar and mystic Al-Ghazali divided the concept of Nafs (soul or self (spirituality)) into three categories based on the Qur’an:

- Nafs Ammarah (12:53) which “exhorts one to freely indulge in gratifying passions and instigates to do evil”

- Nafs Lawammah (75:2) which is “the conscience that directs man towards right or wrong”

- Nafs Mutmainnah (89:27) which is “a self that reaches the ultimate peace”

The medieval Persian philosopher and physician Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi believed in a close relationship between conscience or spiritual integrity and physical health; rather than being self-indulgent, man should pursue knowledge, use his intellect and apply justice in his life. The medieval Islamic philosopher Avicenna, whilst imprisoned in the castle of Fardajan near Hamadhan, wrote his famous isolated-but-awake “Floating Man” sensory deprivation thought experiment to explore the ideas of human self-awareness and the substantiality of the soul; his hypothesis being that it is through intelligence, particularly the active intellect, that God communicates truth to the human mind or conscience. According to the Islamic Sufis conscience allows Allah to guide people to the marifa, the peace or “light upon light” experienced where a Muslim’s prayers lead to a melting away of the self in the inner knowledge of God; this foreshadowing the eternal Paradise depicted in the Qur’ān.

Some medieval Christian scholastics such as Bonaventure made a distinction between conscience as a rational faculty of the mind (practical reason) and inner awareness, an intuitive “spark” to do good, called synderesis arising from a remnant appreciation of absolute good and when consciously denied (for example to perform an evil act), becoming a source of inner torment. Early modern theologians such as William Perkins and William Ames developed a syllogistic understanding of the conscience, where God’s law made the first term, the act to be judged the second and the action of the conscience (as a rational faculty) produced the judgement. By debating test cases applying such understanding conscience was trained and refined (i.e. casuistry).

The Flemish mystic Jan van Ruysbroeck viewed a pure conscience as facilitating “an outflowing losing of oneself in the abyss of that eternal object which is the highest and chief blessedness”

In the 13th century, St. Thomas Aquinas regarded conscience as the application of moral knowledge to a particular case (S.T. I, q. 79, a. 13). Thus, conscience was considered an act or judgment of practical reason that began with synderesis, the structured development of our innate remnant awareness of absolute good (which he categorised as involving the five primary precepts proposed in his theory of Natural Law) into an acquired habit of applying moral principles. According to Singer, Aquinas held that conscience, or conscientia was an imperfect process of judgment applied to activity because knowledge of the natural law (and all acts of natural virtue implicit therein) was obscured in most people by education and custom that promoted selfishness rather than fellow-feeling (Summa Theologiae, I–II, I). Aquinas also discussed conscience in relation to the virtue of prudence to explain why some people appear to be less “morally enlightened” than others, their weak will being incapable of adequately balancing their own needs with those of others.

Aquinas reasoned that acting contrary to conscience is an evil action but an errant conscience is only blameworthy if it is the result of culpable or vincible ignorance of factors that one has a duty to have knowledge of. Aquinas also argued that conscience should be educated to act towards real goods (from God) which encouraged human flourishing, rather than the apparent goods of sensory pleasures. In his Commentary on Aristotle’s Nicomachean EthicsAquinas claimed it was weak will that allowed a non-virtuous man to choose a principle allowing pleasure ahead of one requiring moral constraint.

Thomas A Kempis in the medieval contemplative classic The Imitation of Christ (ca 1418) stated that the glory of a good man is the witness of a good conscience. “Preserve a quiet conscience and you will always have joy. A quiet conscience can endure much, and remains joyful in all trouble, but an evil conscience is always fearful and uneasy.” The anonymous medieval author of the Christian mystical work The Cloud of Unknowing similarly expressed the view that in profound and prolonged contemplation a soul dries up the “root and ground” of the sin that is always there, even after one’s confession and however busy one is in holy things: “therefore, whoever would work at becoming a contemplative must first cleanse his [or her] conscience.” The medieval Flemish mystic John of Ruysbroeck likewise held that true conscience has four aspects that are necessary to render a man just in the active and contemplative life: “a free spirit, attracting itself through love”; “an intellect enlightened by grace”, “a delight yielding propension or inclination” and “an outflowing losing of oneself in the abyss of … that eternal object which is the highest and chief blessedness … those lofty amongst men, are absorbed in it, and immersed in a certain boundless thing.”

Modern

Benedict de Spinoza: moral problems and our emotional responses to them should be reasoned from the perspective of eternity.

Benedict de Spinoza in his Ethics, published after his death in 1677, argued that most people, even those that consider themselves to exercise free will, make moral decisions on the basis of imperfect sensory information, inadequate understanding of their mind and will, as well as emotions which are both outcomes of their contingent physical existence and forms of thought defective from being chiefly impelled by self-preservation. The solution, according to Spinoza, was to gradually increase the capacity of our reason to change the forms of thought produced by emotions and to fall in love with viewing problems requiring moral decision from the perspective of eternity. Thus, living a life of peaceful conscience means to Spinoza that reason is used to generate adequate ideas where the mind increasingly sees the world and its conflicts, our desires and passions sub specie aeternitatis, that is without reference to time. Hegel’s obscure and mystical Philosophy of Mind held that the absolute right of freedom of conscience facilitates human understanding of an all-embracing unity, an absolute which was rational, real and true. Nevertheless, Hegel thought that a functioning State would always be tempted not to recognize conscience in its form of subjective knowledge, just as similar non-objective opinions are generally rejected in science. A similar idealist notion was expressed in the writings of Joseph Butler who argued that conscience is God-given, should always be obeyed, is intuitive, and should be considered the “constitutional monarch” and the “universal moral faculty”: “conscience does not only offer itself to show us the way we should walk in, but it likewise carries its own authority with it.” Butler advanced ethical speculation by referring to a duality of regulative principles in human nature: first,”self-love” (seeking individual happiness) and second, “benevolence” (compassion and seeking good for another) in conscience (also linked to the agape of situational ethics). Conscience tended to be more authoritative in questions of moral judgment, thought Butler, because it was more likely to be clear and certain (whereas calculations of self-interest tended to probable and changing conclusions). John Selden in his Table Talk expressed the view that an awake but excessively scrupulous or ill-trained conscience could hinder resolve and practical action; it being “like a horse that is not well wayed, he starts at every bird that flies out of the hedge”.

As the sacred texts of ancient Hindu and Buddhist philosophy became available in German translations in the 18th and 19th centuries, they influenced philosophers such as Schopenhauer to hold that in a healthy mind only deeds oppress our conscience, not wishes and thoughts; “for it is only our deeds that hold us up to the mirror of our will”; the good conscience, thought Schopenhauer, we experience after every disinterested deed arises from direct recognition of our own inner being in the phenomenon of another, it affords us the verification “that our true self exists not only in our own person, this particular manifestation, but in everything that lives. By this the heart feels itself enlarged, as by egotism it is contracted.”

Immanuel Kant, a central figure of the Age of Enlightenment, likewise claimed that two things filled his mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the oftener and more steadily they were reflected on: “the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me … the latter begins from my invisible self, my personality, and exhibits me in a world which has true infinity but which I recognise myself as existing in a universal and necessary (and not only, as in the first case, contingent) connection.” The ‘universal connection’ referred to here is Kant’s categorical imperative: “act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” Kant considered critical conscience to be an internal court in which our thoughts accuse or excuse one another; he acknowledged that morally mature people do often describe contentment or peace in the soul after following conscience to perform a duty, but argued that for such acts to produce virtue their primary motivation should simply be duty, not expectation of any such bliss. Rousseau expressed a similar view that conscience somehow connected man to a greater metaphysical unity. John Plamenatz in his critical examination of Rousseau’s work considered that conscience was there defined as the feeling that urges us, in spite of contrary passions, towards two harmonies: the one within our minds and between our passions, and the other within society and between its members; “the weakest can appeal to it in the strongest, and the appeal, though often unsuccessful, is always disturbing. However, corrupted by power or wealth we may be, either as possessors of them or as victims, there is something in us serving to remind us that this corruption is against nature.”

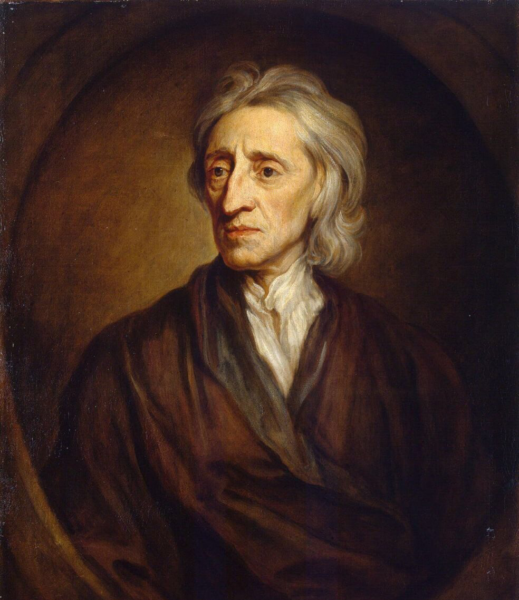

John Locke viewed the widespread social fact of conscience as a justification for natural rights.

Other philosophers expressed a more sceptical and pragmatic view of the operation of “conscience” in society. John Locke in his Essays on the Law of Nature argued that the widespread fact of human conscience allowed a philosopher to infer the necessary existence of objective moral laws that occasionally might contradict those of the state. Locke highlighted the metaethics problem of whether accepting a statement like “follow your conscience” supports subjectivist or objectivist conceptions of conscience as a guide in concrete morality, or as a spontaneous revelation of eternal and immutable principles to the individual: “if conscience be a proof of innate principles, contraries may be innate principles; since some men with the same bent of conscience prosecute what others avoid.” Thomas Hobbes likewise pragmatically noted that opinions formed on the basis of conscience with full and honest conviction, nevertheless should always be accepted with humility as potentially erroneous and not necessarily indicating absolute knowledge or truth. William Godwin expressed the view that conscience was a memorable consequence of the “perception by men of every creed when the descend into the scene of busy life” that they possess free will. Adam Smith considered that it was only by developing a critical conscience that we can ever see what relates to ourselves in its proper shape and dimensions; or that we can ever make any proper comparison between our own interests and those of other people. John Stuart Mill believed that idealism about the role of conscience in government should be tempered with a practical realisation that few men in society are capable of directing their minds or purposes towards distant or unobvious interests, of disinterested regard for others, and especially for what comes after them, for the idea of posterity, of their country, or of humanity, whether grounded on sympathy or on a conscientious feeling. Mill held that certain amount of conscience, and of disinterested public spirit, may fairly be calculated on in the citizens of any community ripe for representative government, but that “it would be ridiculous to expect such a degree of it, combined with such intellectual discernment, as would be proof against any plausible fallacy tending to make that which was for their class interest appear the dictate of justice and of the general good.”

Josiah Royce (1855–1916) built on the transcendental idealism view of conscience, viewing it as the ideal of life which constitutes our moral personality, our plan of being ourself, of making common sense ethical decisions. But, he thought, this was only true insofar as our conscience also required loyalty to “a mysterious higher or deeper self.” In the modern Christian tradition this approach achieved expression with Dietrich Bonhoeffer who stated during his imprisonment by the Nazis in World War II that conscience for him was more than practical reason, indeed it came from a “depth which lies beyond a man’s own will and his own reason and it makes itself heard as the call of human existence to unity with itself.” For Bonhoeffer a guilty conscience arose as an indictment of the loss of this unity and as a warning against the loss of one’s self; primarily, he thought, it is directed not towards a particular kind of doing but towards a particular mode of being. It protests against a doing which imperils the unity of this being with itself.Conscience for Bonhoeffer did not, like shame, embrace or pass judgment on the morality of the whole of its owner’s life; it reacted only to certain definite actions: “it recalls what is long past and represents this disunion as something which is already accomplished and irreparable”. The man with a conscience, he believed, fights a lonely battle against the “overwhelming forces of inescapable situations” which demand moral decisions despite the likelihood of adverse consequences.Simon Soloveychik has similarly claimed that the truth distributed in the world, as the statement about human dignity, as the affirmation of the line between good and evil, lives in people as conscience.

As Hannah Arendt pointed out, however, (following the utilitarian John Stuart Mill on this point): a bad conscience does not necessarily signify a bad character; in fact only those who affirm a commitment to applying moral standards will be troubled with remorse, guilt or shame by a bad conscience and their need to regain integrity and wholeness of the self. Representing our soul or true self by analogy as our house, Arendt wrote that “conscience is the anticipation of the fellow who awaits you if and when you come home.” Arendt believed that people who are unfamiliar with the process of silent critical reflection about what they say and do will not mind contradicting themselves by an immoral act or crime, since they can “count on its being forgotten the next moment;” bad people are not full of regrets. Arendt also wrote eloquently on the problem of languages distinguishing the word consciousness from conscience. One reason, she held, was that conscience, as we understand it in moral or legal matters, is supposedly always present within us, just like consciousness: “and this conscience is also supposed to tell us what to do and what to repent; before it became the lumen naturale or Kant’s practical reason, it was the voice of God.”

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein, as a self-professed adherent of humanism and rationalism, likewise viewed an enlightened religious person as one whose conscience reflects that he “has, to the best of his ability, liberated himself from the fetters of his selfish desires and is preoccupied with thoughts, feelings and aspirations to which he clings because of their super-personal value.” Einstein often referred to the “inner voice” as a source of both moral and physical knowledge: “Quantum mechanics is very impressive. But an inner voice tells me that it is not the real thing. The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings one closer to the secrets of the Old One. I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice.”

Simone Weil who fought for the French resistance (the Maquis) argued in her final book The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind that for society to become more just and protective of liberty, obligations should take precedence over rights in moral and political philosophy and a spiritual awakening should occur in the conscience of most citizens, so that social obligations are viewed as fundamentally having a transcendent origin and a beneficent impact on human character when fulfilled. Simone Weil also in that work provided a psychological explanation for the mental peace associated with a good conscience: “the liberty of men of goodwill, though limited in the sphere of action, is complete in that of conscience. For, having incorporated the rules into their own being, the prohibited possibilities no longer present themselves to the mind, and have not to be rejected.”

Alternatives to such metaphysical and idealist opinions about conscience arose from realist and materialist perspectives such as those of Charles Darwin. Darwin suggested that “any animal whatever, endowed with well-marked social instincts, the parental and filial affections being here included, would inevitably acquire a moral sense or conscience, as soon as its intellectual powers had become as well, or as nearly as well developed, as in man.” Émile Durkheim held that the soul and conscience were particular forms of an impersonal principle diffused in the relevant group and communicated by totemic ceremonies. AJ Ayer was a more recent realist who held that the existence of conscience was an empirical question to be answered by sociological research into the moral habits of a given person or group of people, and what causes them to have precisely those habits and feelings. Such an inquiry, he believed, fell wholly within the scope of the existing social sciences. George Edward Moore bridged the idealistic and sociological views of ‘critical’ and ‘traditional’ conscience in stating that the idea of abstract ‘rightness’ and the various degrees of the specific emotion excited by it are what constitute, for many persons, the specifically ‘moral sentiment’ or conscience. For others, however, an action seems to be properly termed ‘internally right’, merely because they have previously regarded it as right, the idea of ‘rightness’ being present in some way to his or her mind, but not necessarily among his or her deliberately constructed motives.

The French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir in A Very Easy Death (Une mort très douce, 1964) reflects within her own conscience about her mother’s attempts to develop such a moral sympathy and understanding of others.

“The sight of her tears grieved me; but I soon realised that she was weeping over her failure, without caring about what was happening inside me … We might still have come to an understanding if, instead of asking everybody to pray for my soul, she had given me a little confidence and sympathy. I know now what prevented her from doing so: she had too much to pay back, too many wounds to salve, to put herself in another’s place. In actual doing she made every sacrifice, but her feelings did not take her out of herself. Besides, how could she have tried to understand me since she avoided looking into her own heart? As for discovering an attitude that would not have set us apart, nothing in her life had ever prepared her for such a thing: the unexpected sent her into a panic, because she had been taught never to think, act or feel except in a ready-made framework.”— Simone de Beauvoir. A Very Easy Death. Penguin Books. London. 1982. p. 60.

Michael Walzer claimed that the growth of religious toleration in Western nations arose amongst other things, from the general recognition that private conscience signified some inner divine presence regardless of the religious faith professed and from the general respectability, piety, self-limitation, and sectarian discipline which marked most of the men who claimed the rights of conscience. Walzer also argued that attempts by courts to define conscience as a merely personal moral code or as sincere belief, risked encouraging an anarchy of moral egotisms, unless such a code and motive was necessarily tempered with shared moral knowledge: derived either from the connection of the individual to a universal spiritual order, or from the common principles and mutual engagements of unselfish people. Ronald Dworkin maintains that constitutional protection of freedom of conscience is central to democracy but creates personal duties to live up to it: “Freedom of conscience presupposes a personal responsibility of reflection, and it loses much of its meaning when that responsibility is ignored. A good life need not be an especially reflective one; most of the best lives are just lived rather than studied. But there are moments that cry out for self-assertion, when a passive bowing to fate or a mechanical decision out of deference or convenience is treachery, because it forfeits dignity for ease.” Edward Conze stated it is important for individual and collective moral growth that we recognise the illusion of our conscience being wholly located in our body; indeed both our conscience and wisdom expand when we act in an unselfish way and conversely “repressed compassion results in an unconscious sense of guilt.”

The philosopher Peter Singer considers that usually when we describe an action as conscientious in the critical sense we do so in order to deny either that the relevant agent was motivated by selfish desires, like greed or ambition, or that he acted on whim or impulse.

Moral anti-realists debate whether the moral facts necessary to activate conscience supervene on natural facts with a posteriori necessity; or arise a priori because moral facts have a primary intension and naturally identical worlds may be presumed morally identical. It has also been argued that there is a measure of moral luck in how circumstances create the obstacles which conscience must overcome to apply moral principles or human rights and that with the benefit of enforceable property rights and the rule of law, access to universal health care plus the absence of high adult and infant mortality from conditions such as malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and famine, people in relatively prosperous developed countries have been spared pangs of conscience associated with the physical necessity to steal scraps of food, bribe tax inspectors or police officers, and commit murder in guerrilla wars against corrupt government forces or rebel armies. Scrutton has claimed that true understanding of conscience and its relationship with morality has been hampered by an “impetuous” belief that philosophical questions are solved through the analysis of language in an area where clarity threatens vested interests. Susan Sontag similarly argued that it was a symptom of psychological immaturity not to recognise that many morally immature people willingly experience a form of delight, in some an erotic breaking of taboo, when witnessing violence, suffering and pain being inflicted on others. Jonathan Glover wrote that most of us “do not spend our lives on endless landscape gardening of our self” and our conscience is likely shaped not so much by heroic struggles, as by choice of partner, friends and job, as well as where we choose to live. Garrett Hardin in a famous article called tragedy of the commons argued that any instance in which society appeals to an individual exploiting a commons to restrain himself or herself for the general good-by means of his or her conscience– merely sets up a system which, by selectively diverting societal power and physical resources to those lacking in conscience, while fostering guilt (including anxiety about his or her individual contribution to over-population) in people acting upon it, actually works toward the elimination of conscience from the race.

John Ralston Saul expressed the view in The Unconscious Civilization that in contemporary developed nations many people have acquiesced in turning over their sense of right and wrong, their critical conscience, to technical experts; willingly restricting their moral freedom of choice to limited consumer actions ruled by the ideology of the free market, while citizen participation in public affairs is limited to the isolated act of voting and private-interest lobbying turns even elected representatives against the public interest.

Some argue on religious or philosophical grounds that it is blameworthy to act against conscience, even if the judgement of conscience is likely to be erroneous (say because it is inadequately informed about the facts, or prevailing moral (humanist or religious), professional ethical, legal and human rights norms). Failure to acknowledge and accept that conscientious judgements can be seriously mistaken, may only promote situations where one’s conscience is manipulated by others to provide unwarranted justifications for non-virtuous and selfish acts; indeed, insofar as it is appealed to as glorifying ideological content, and an associated extreme level of devotion, without adequate constraint of external, altruistic, normative justification, conscience may be considered morally blind and dangerous both to the individual concerned and humanity as a whole. Langston argues that philosophers of virtue ethics have unnecessarily neglected conscience for, once conscience is trained so that the principles and rules it applies are those one would want all others to live by, its practise cultivates and sustains the virtues; indeed, amongst people in what each society considers to be the highest state of moral development there is little disagreement about how to act. Emmanuel Levinas viewed conscience as a revelatory encountering of resistance to our selfish powers, developing morality by calling into question our naive sense of freedom of will to use such powers arbitrarily, or with violence, this process being more severe the more rigorously the goal of our self was to obtain control. In other words, the welcoming of the Other, to Levinas, was the very essence of conscience properly conceived; it encouraged our ego to accept the fallibility of assuming things about other people, that selfish freedom of will “does not have the last word” and that realising this has a transcendent purpose: “I am not alone … in conscience I have an experience that is not commensurate with any a priori [see a priori and a posteriori] framework-a conceptless experience.”

Adapted from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia